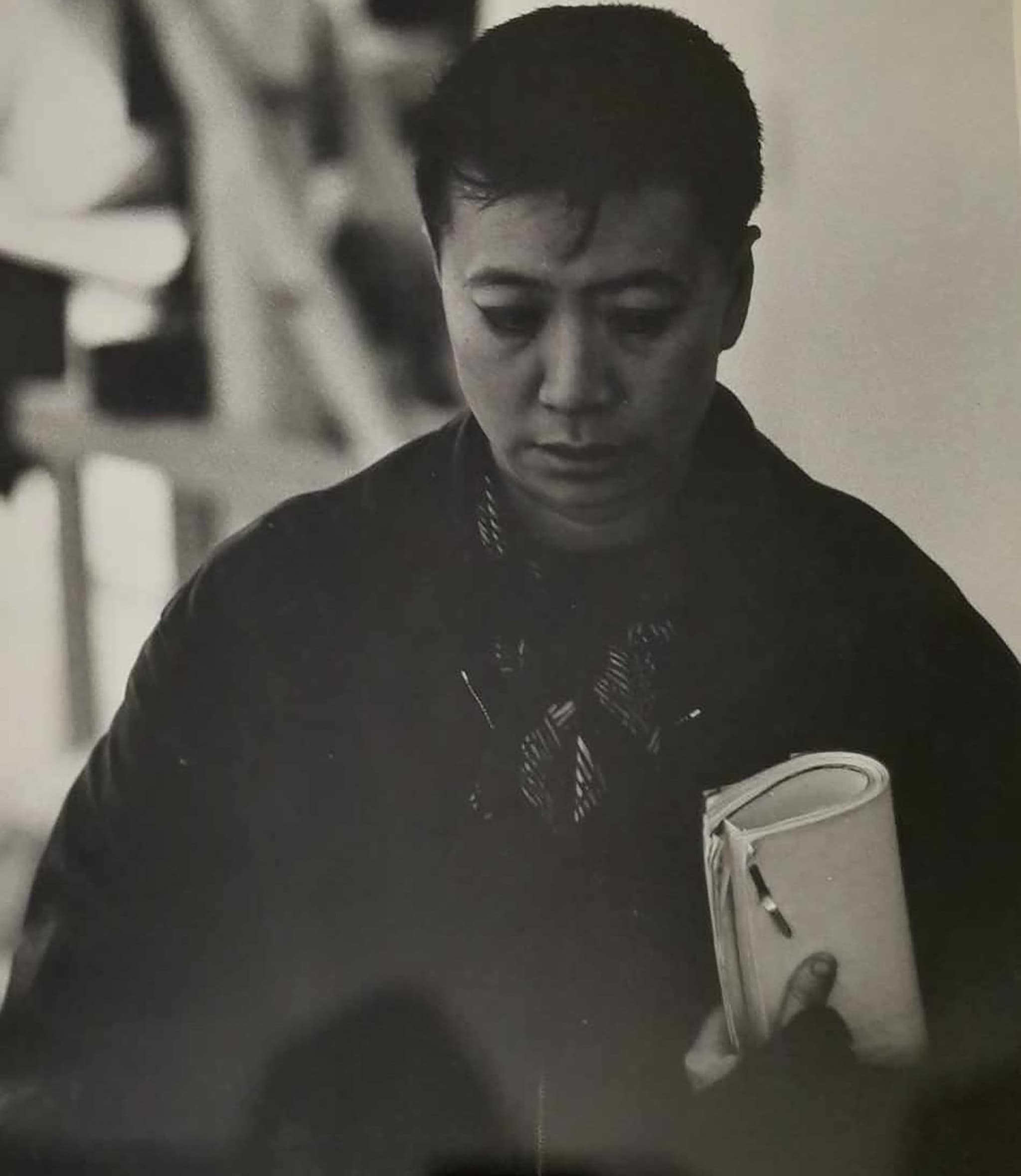

We Ate a Sheep. We Lost the Plot: Shu Lea Cheang Shu Lea Cheang, Lauren Cornell, and Tiffany Sia in conversation

November 2024

A self-proclaimed “floating digital agent” who is now settled in Paris, born in Taiwan and “formatted in the United States,” artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang has, since the 1990s, defied categorization through a practice that rethinks normativity, hacks gender, and subverts the collective spaces in which media operate. Soon to embark on a road trip across the United States to screen a remastered 35mm print of her film Fresh Kill (1994) at art houses and independent cinemas while preparing KI$$ KI$$, her major survey exhibition at Haus der Kunst, Munich, opening in February 2025, Cheang sat down with curator Lauren Cornell and artist Ti!any Sia to delve into the themes that have long fueled her networked installations, internet art projects, and feature films. Together, they discuss Cheang’s continuous engagement with technology, speculative sci-fi narratives, and the evolving topics of surveillance, bioengineering, and subjectivity across physical and virtual spaces. They also examine her radical reclamation of pornography as a catalyst for empowerment from a queer and feminist perspective, and consider the enduring role of media activism in a world shaped by pervasive monitoring and control.

LAUREN CORNELL

Where are you at the moment, Shu Lea?

SHU LEA CHEANG

I’m in Paris. I’ve been based here for twenty years now, since I left New York.

LAUREN

Right. Well, as a starting point, let’s discuss your forthcoming survey at Haus der Kunst in Munich, opening in February of next year, which will include new works but also, as the exhibition curator Sarah Johanna Theurer says, “new landscape formations” of early works. As I understand it, this means you’re going to be rethinking existing pieces, which strikes me as appropriate given how your work has been so prescient in its framings of surveillance, bioengineering, and subjectivity as it shape- shifts across IRL and virtual states. When you started out in your career, all of these ideas were arguably perceived as more marginal, but they’re now central aspects of our lives. Could you speak about your process of updating and evolving your older works—why you’re doing it, and how you see them resonating in the present?

SHU LEA

When I knew that I would be given three gallery spaces at Haus der Kunst, all quite big, we decided that each room would be its own “unit” in which I might combine two or more works, perhaps some newer and some older, giving the latter a new meaning. Whenever technology is involved, remounting an existing piece always prompts you to ask yourself how much you want to rethink—in terms of conservation, the interface, the so$ware version, the digital versus the analog, and so on. For me, it’s less about trying to get back to the “original” work, and more about updating it, knowing that, at least in my case, much of the work doesn’t really physically exist in an object- oriented sense. I also realize that a lot of my work poses di!erent threads. Maybe a certain medium or concept or technology in an older work is also present in a new one. This survey show allows me to make those links.

TIFFANY SIA

I’m curious about how you’ve presented your film works earlier in your career versus more recently. You’ve previously not wanted to show your feature-length cinematic works in gallery spaces, but that has changed—for instance you showed Fresh Kill (1994), I.K.U. (2000), FLUIDØ (2017), and UKI (2023) at Project Native Informant, London, in March of this year. In the past, you’ve reserved these works for purely cinematic, theatrical contexts, as when you showed I.K.U. at Sundance in 2000, or FLUIDØ at the Flaherty Film Seminar in 2023. What is unique and special for you about the context— the ritual, even—of the cinema, especially as you take Fresh Kill on a road trip across the

United States to independent art houses this fall?

SHU LEA

I studied cinema at NYU, and always felt I was meant to be a filmmaker and that it was accidental that I became an artist. But I did become one when I had my first-ever solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 1990, presenting Color Schemes (1990).

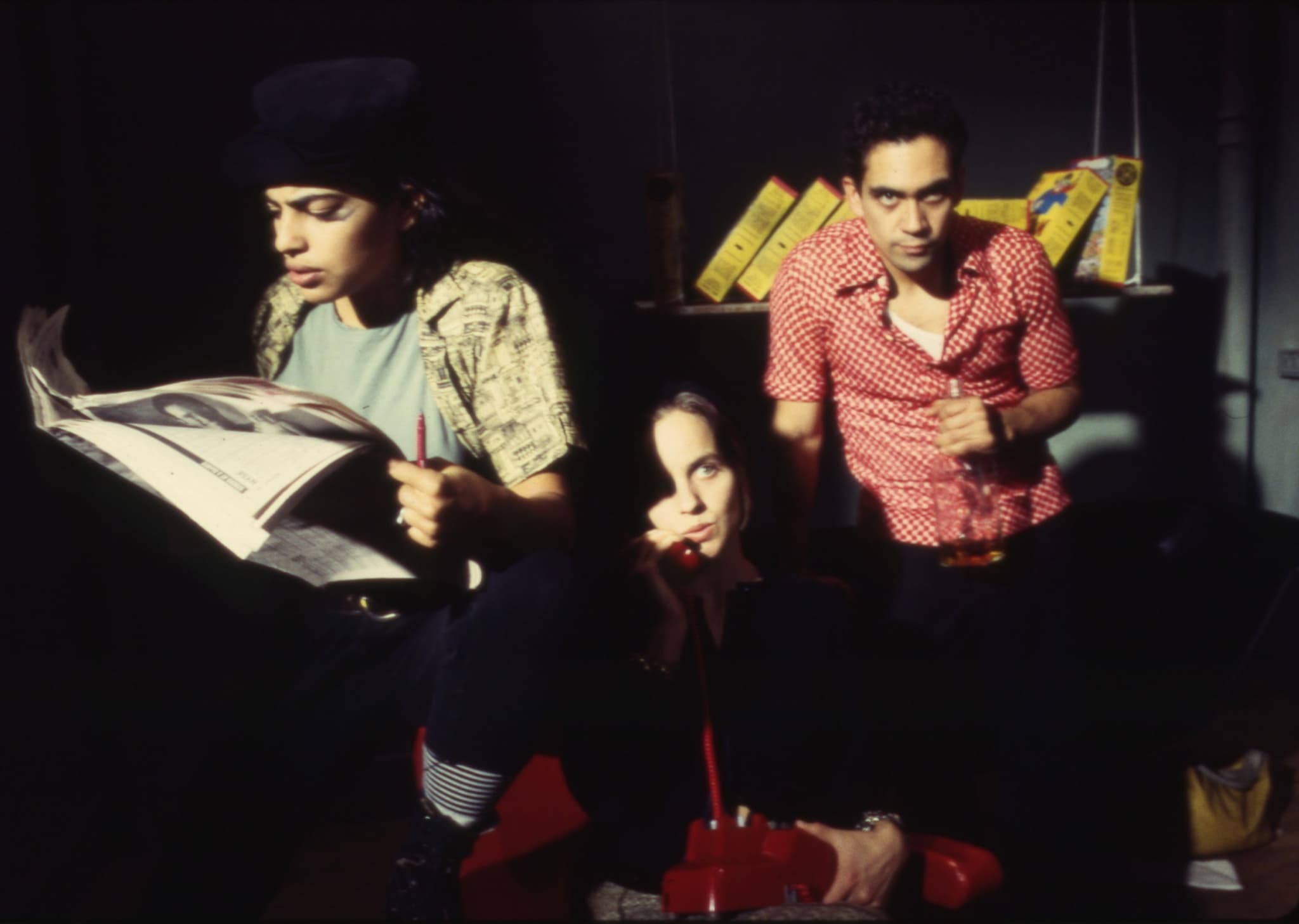

In the 1980s, we had public-access television, and portable video cameras became accessible, so I learned about video as a medium of expression while still wanting to make films. At the time I was following masters like Bill Viola, Nam June Paik, and the genre of video art more broadly, which was presenting video and video installations in galleries, using di!erent devices and technologies, not just projecting onto screens. I didn’t really come from a background of making films for art exhibition spaces; I always wanted to make films for cinema screenings. For me, cinema is the way to access the general public. For my first feature film, Fresh Kill, we struggled to shoot it in 35mm, figuring that that’s the format necessary to show it in a real cinema.

At the time, it was very political for an independent woman filmmaker to be working in 35mm. Yet somehow, within a three-decade span, I managed to make four feature films, and getting each film made had its own story. FLUIDØ took me seventeen years to make. UKI took me fourteen years to realize in terms of raising the money. And I do still cherish the real cinema experience, as when last June, I had a one-week screening of these four films under the heading “Sci-Fi Queer New Cinema: Shu Lea Cheang (1994–2023)” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In the presentation you mentioned at Project Native Informant, the gallery space was set up with special seating, and each film was screened on a scheduled basis. So, for a gallery experience, it was cinema-esque.

TIFFANY

“Sci-Fi New Queer Cinema” elaborates on B. Ruby Rich’s 2013 book New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut, right? You’ve talked about how you felt your work is distinct from Rich’s concept of New Queer Cinema because you’re infusing this new genre with science fiction. I sense that this distinction is very important to you. Sci-fi intersects with so much of your practice and the themes that concern you, from genre filmmaking (very much part of cinema studies), to new media art, to queer aesthetics. Your work in new media aesthetics sometimes exceeds cinematic forms and ventures into other types of “screen” culture such as net art. What does Sci-Fi New Queer Cinema mean to you? And what do you perceive is at stake when it comes to the genre of sci-fi?

SHU LEA

B. Ruby Rich coined the term New Queer Cinema in 1992. It includes a young generation of queer filmmakers, which at the time I considered myself part of, although always with a bit of gap. Rich did include I.K.U. in the book with an article she wrote for I.K.U.’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 2000. For years, I was quite happy to be considered part of this genre of filmmaking, but I realized my “dri$ing” into the sci-fi imagination set me apart from being simply called New Queer.

I am indebted to Samuel R. Delany’s sci-fi Queer Vision and the fictionalized portraits of his sexing self. We did collaborate in the beginning of I.K.U.’s scripting, but it didn’t work out as the project got relocated to Tokyo’s underground. Delany writes about sexual desire in a raw, naked way, o$en depicting explosive sexual encounters. I paid homage to him with I.K.U. and FLUIDØ.

UKI, which I conceived as a sequel to I.K.U., was grounded in bioengineering research and inspired by Greg Bear’s Blood Music (1985). My sci-fi is a rebellion against the prevailing science fiction, which is pretty male-centered. Also, quite a lot about fears of the machine, the robot, or the replicant taking over the world. There’s a lot of complexity in the human fear of losing control—more than ever now, with the advent of AI.

TIFFANY

Preparing for this interview, I reread a bit of Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999). I knew Delany is a big inspiration for you. That book in particular contains all these descriptions of porn cinemas in the Times Square of that era, but he’s writing less about the images being shown on the screen and more about the whole culture around watching them, the mixing of people that happens in the cinemas showing erotic images. I’ve been thinking about your use of pornography in this context.

In B. Ruby Rich’s chapter on your work, she talks about how I.K.U. was shown at Sundance, and that the audience was scandalized. 2 That tension of what it means to show a pornographic image in the cinema, a shared public space, is interesting, especially as you’ve extended these explorations of the forbidden in your work. But with pornographic images themselves, particularly around queerness and the body as a subversive tool, you also lay bare the racial politics of sexualized bodies on screen —including the intense fantasies around the Asian female. Can you talk about your interest in working with, subverting, and "aunting taboo images in porn, and treating the pornographic as both image and motif? I’m curious what the forbidden unlocks for you.

SHU LEA

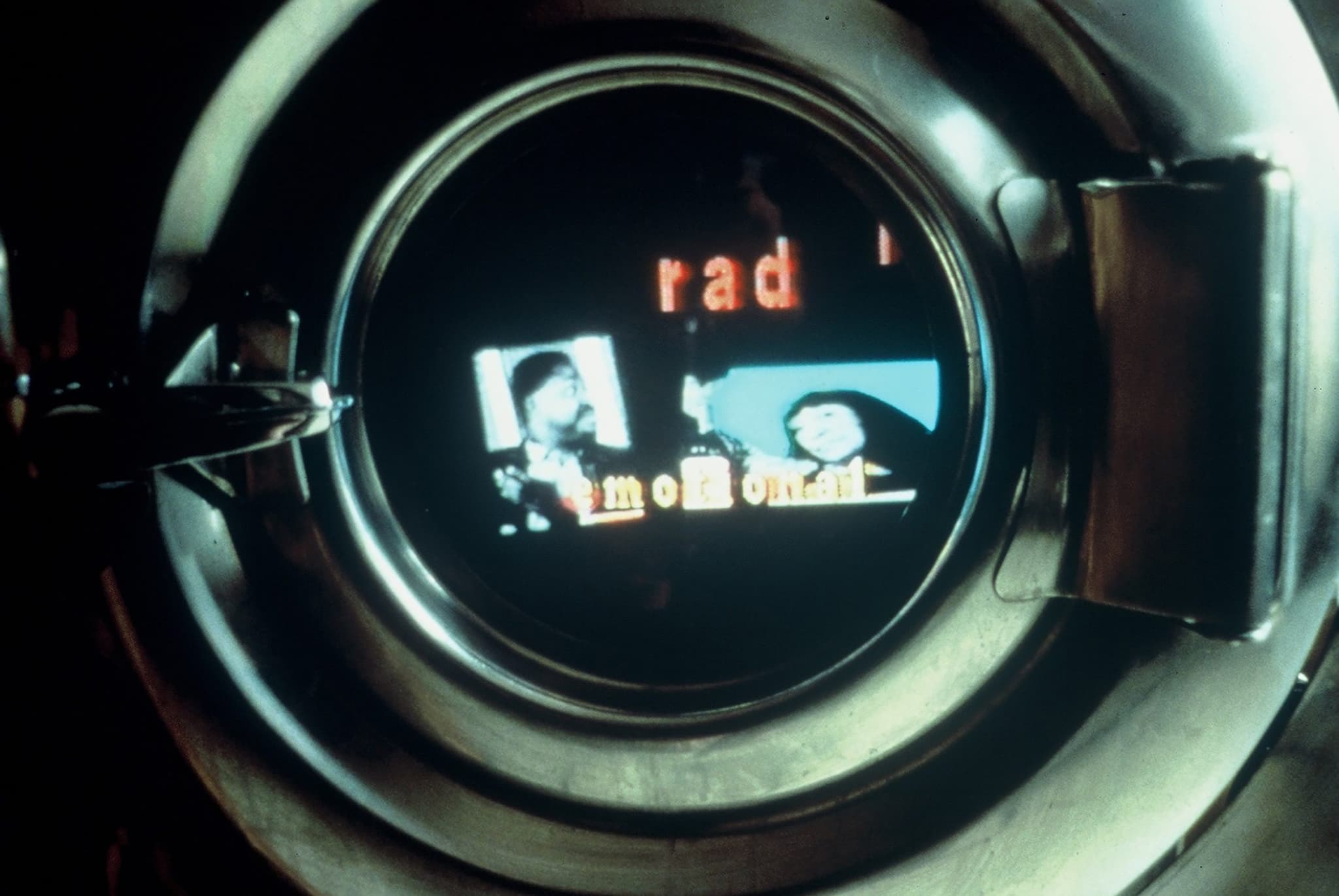

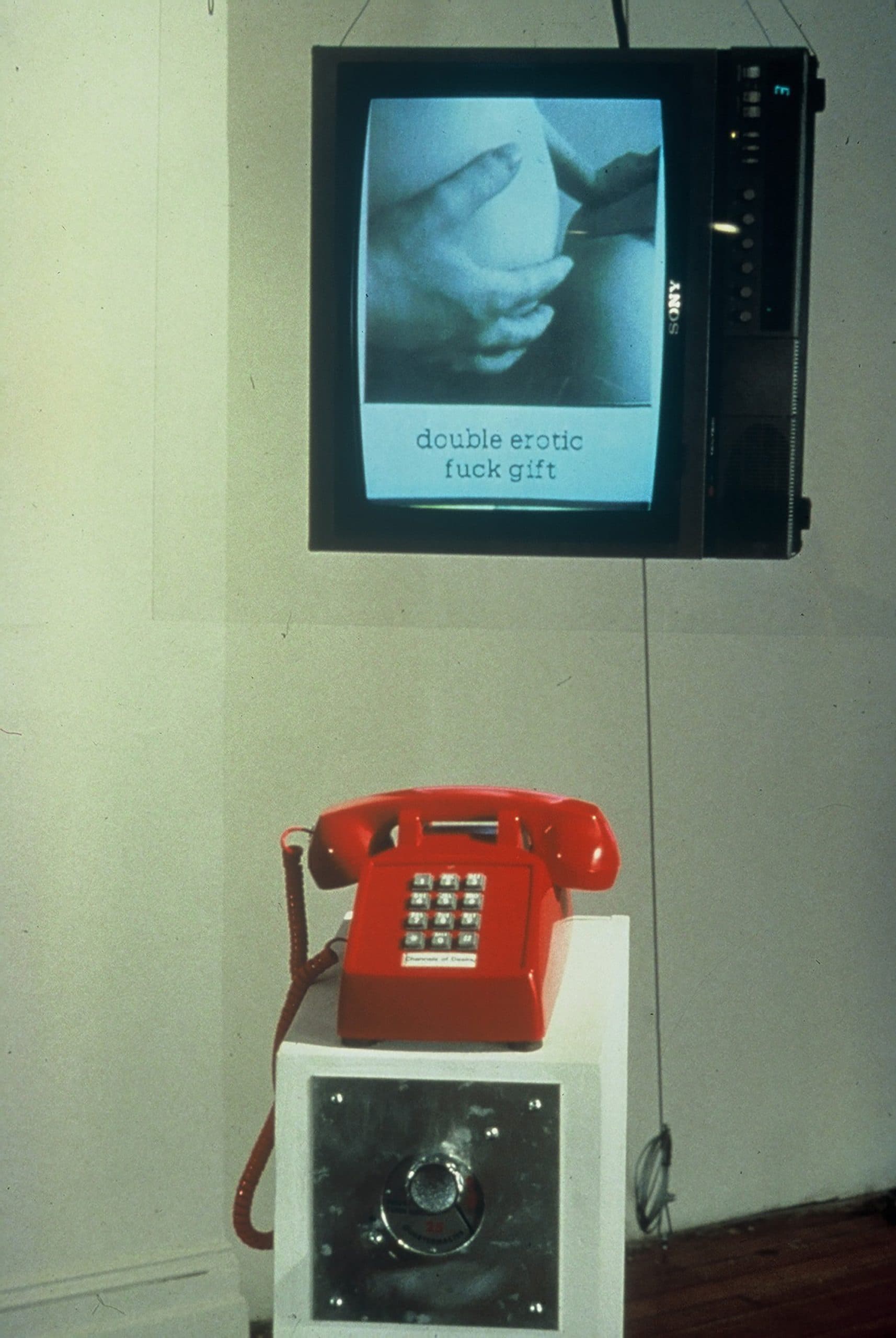

I was familiar with the pornographic cinema scene in the 1980s and 1990s because I was working as a film editor right on Times Square at 1600 Broadway, and also as a boom operator in some classic porn filmmaking 3 when they’d come to New York to shoot for a weekend. I did all kinds of jobs on set, mostly independent filmmaking. Times Square cinemas, particularly the theaters showing pornography, did affect me, and triggered inspiration for some of my works. For example, Those Fluttering Objects of Desire (1992–93) derived from the viewing booths in the adult shops. In this work, I inverted the typical male gaze by inviting sixteen women to take black-and-white “selfies” and address issues of sexual desire. That was the artistic approach.

Later, I was invited by Japanese producer Takashi Asai of Uplink Co. to make I.K.U. in Tokyo. Asai–san wanted to challenge the Japanese censorship rules, under which you cannot show any sexual organs (for instance a penis or a vagina), either moving or not. When he invited me to Tokyo to make I.K.U., we set out specifically to make a porn film. When it was to be shown in Japan, the censor blacked out 150 sensitive spots, literally using a black marker on the 35mm film print. Luckily, I have never seen that version.

Right from the beginning, it was clear to me that I’d set out to make porn for women so as to reclaim the genre. Around 2004 or 2005 there was a big moment of women making pornography; we started a “post-porn” genre, manifested by the Post Porn Politics conference in Berlin in 2006, organized by Tim Stüttgen, and the FeminismoPornoPunk program organized by Paul B. Preciado at Arteleku in San Sebastián, Spain, in 2008. I do feel I belong to this post-porn community, as it’s about reclaiming the medium, grabbing a camera with your own hands. I see my use of pornography as a mode of resistance. In FLUIDØ, fluid from ejaculation (male and female) flows freely, facing the audience, who encounter these on-your-face explosions. I want the audience to experience collective orgasms, and that can only happen in the cinemas where my films are screened.

LAUREN

Pornography, at a certain point, was perceived as anti-feminist, and so women artists who made it were seen as heretical. I do appreciate how significant the artistic turn is where you’re taking porn into your own hands as a means of resetting its terms and power dynamics. Your work is so incisive for how it others many different strategies for resistance, and particularly media resistance, over periods of time.

I know that you worked at Paper Tiger TV. I also volunteered there at the very end of the 1990s, right as we were anticipating Y2K. That collective is grounded in notions of opposition to an earlier media paradigm, namely

mainstream (then, that meant cable) TV. Their mission was to provide an alternative to the programming on mainstream TV, aiming to “overthrow corporate media.” Personally, even though times have changed, I still carry that ethos with me in my work—that core desire to support artistic uses of, or alternatives to, commercial media. Can you talk about whether you still feel in"uenced by that moment in time, how you look back at it, and how you carry its ethos forward?

SHU LEA

Paper Tiger TV was definitely part of my formation in New York. I lived in the East Village in the 1980s and 1990s, twenty years. It was a turbulent time. Paper Tiger TV catered to a very special need related to media criticism and activism. The 1980s, for me, were about protesting on the streets. There were a lot of street actions, all kinds of different movements. And, crucially, the portable video camera was becoming highly accessible. Many groups were able to pick up video cameras and document themselves, directly challenging mainstream media’s twisted reporting on demonstrations taking place on the streets. I was working toward my MA degree in cinema studies at NYU with a focus on New American Cinema, and there was also a No Wave underground filmmaking movement on the Lower East Side, with independent cinema on the rise. My academic training happened in tandem with being a media activist and engaging with the experimental filmmakers and theater groups in New York’s downtown scene.

LAUREN

When you started to work with the internet, you became part of the first generation of artists to embrace its new possibilities and interrogate the new systems of power and control that came with it. Key to your work starting from that moment with Brandon (1998– 99), which was an early and groundbreaking net art project, was your exploration of surveillance, which has run through your practice and was also integral to 3x3x6 (2019). This was an incredible installation, and I perceived a really clear line from your exploration of notions of gendered and racialized bodies being policed and monitored in Brandon through to 3x3x6, which was exploring these subjects in a more contemporary way via conditions of facial recognition technologies and AI. Can you speak about your preoccupation with surveillance and your concerns about it now, as manifested in recent works?

SHU LEA

In 1994 I released my first feature film, Fresh Kill, which was shot in 35mm, but switched to digital editing as it became available. That was a big transition. I then experienced my first internet artwork, making a pilgrimage to Columbia University’s library to see Antoni

Muntadas’s The File Room (1994–98). At that time, spending hours on the internet using the Mosaic browser was completely novel. I quickly jumped onto the information superhighway, but took a detour to reconsider race and gender in the cyberspace. “Homesteading” cyberspace became my mission. Brandon relocated Brandon Teena from Nebraska to cyberspace, and explored issues of gender fusion and techno- bodies in both public space and cyberspace. 4

Speaking of the connection between Brandon and 3x3x6, in 1998 I had a residency at the Waag Society in Amsterdam, where Brandon’s web production and programming took place. We visited the Arnhem Koepel Prison, which was built according to Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon principle (1785) and remained functional at the time of our visit. I was quite a!ected by this all-encompassing surveillance structure, which translated into Brandon’s panopticon interface. By the time I made 3x3x6 in 2019, twenty years later, the inspiration to revisit this subject came from the Palazzo delle Prigioni (Prisons’ Palace), where Taiwan’s presentation of my work at the Venice Biennale took place in four former cells. 5 When I started researching the venue, I discovered that Casanova had been imprisoned there; he managed to escape, and it’s from that particular story that I developed the ten cases, the ten films, and the installation. In 3x3x6, I turned the architectural panopticon into a digital panopticon with facial recognition surveillance, as we live in a controlled society. But I set out to reverse the apparatus of the panopticon. In Room A at the Prigioni, ten projectors were installed to face a tower, projecting the introduction of the ten cases. This inverse panopticon without the all-seeing eye atop the tower demonstrated tactics of resistance.

TIFFANY

You are tracing such consistent themes and strong undercurrents in your works, going back decades, especially around this notion of the panopticon, the multiscreen, and the simultaneity of the surveillance gaze. When you’re describing this, there’s a hyper-local specificity that you pull from. Of course you’re also talking about a global phenomenon, but not as a vague globalism—you’re talking about a universal pressure of surveillance on every level of every locality.

I know you were a producer for a 1990 compilation program titled Will Be Televised: Video Documents from Asia for Deep Dish TV, and Taiwan: The Generation a!er Martial Law (1990), the latter which I actually wrote a short piece about last year; it was a fi$y-eight-minute program of protest footage compiled from various artists captured during a highly pivotal year, 1989, this intense Cold War moment in Taiwanese politics. Coming to your work Making News / Making History: Live from Tiananmen Square (1989), we see this theme of forbidden images and video documents being an ongoing occupation for you. Throughout, you use the camera as a tool of subversion, to see outside of social, state-powered narratives. I cannot help but connect this point to the fact that you’re a filmmaker who was born during martial law in Taiwan. There’s something about this origin and ethos of fugitivity and resistance that continues in your later work as you extend those interests into internet culture and various sites of lo-fi activism.

I’m so curious what it felt like for you to bring your camera to witness ACT UP protestors putting their bodies on the front lines in New York, or in Tiananmen Square. Can you describe your experience of being connected to these communities?

SHU LEA

The trip to Tiananmen Square was accidental!

In 1989, when all the student demonstrations were happening in China, I was with artist Ai Weiwei and filmmaker Chen Kaige demonstrating in New York, supporting Tiananmen Square’s occupation by the students. Both Weiwei and Kaige were very emotional and would have rushed back to China to join in, but they were worried they would be forced to stay. So they asked if I would go, as I held an American green card at the time. Kaige basically just gave me a JVC camera—I think it had been donated to him by the Japanese company—and said, “Take this camera and go to China.”

I managed to enter China with a tourist visa, and, following Kaige’s directions, went to his father, who worked at a Beijing film studio. His father gave me a room and a bicycle to get around. I then spent two weeks at Tiananmen Square, being with the students and documenting the scenes every day. At the time, an Asian woman holding a video camera was an unusual sight.

Surveillance cameras were installed all around Tiananmen Square, but I had no idea what kinds of images they were capturing until after the June Fourth massacre, when the central government television station finally released the footage. I came back to New York and produced the five-channel installation Making News / Making History: Live from Tiananmen Square, which mixed the footage I’d captured with the CCTV surveillance footage. I realized the power of the surveillance camera, given how the Chinese government set them up, documented all the actions, then used the results after June Fourth to “prove” that the massacre didn’t happen. I also realized there already existed video activism in Asia at the time. Activists were using video cameras to document, to counter mainstream media. The accumulation of the video material serves as a witness to this era of resistance via moving images. In 1990, I received a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts to compile protest videos from five different countries from the 1980s, thus the five-hour series titled Will Be Televised, which was made for and distributed by Deep Dish TV, a grassroot video satellite network.

LAUREN

It’s incredible to hear that story. I also have to say, one of the first times I met Ti!any in person was in Hong Kong in 2019, and she was carrying a big video camera rig and wearing a face mask, coming out of the anti-government, pro-democracy protests–taking a break for a moment to eat dinner, with our group of friends.

SHU LEA

The anti-ELAB (anti-Extradition-Law- Amendment-Bill) movement in Hong Kong during 2019–20 also used the encrypted Telegram app to mobilize the protestors. It was a new tactics borne out of the social network generation.

LAUREN

Resistance and its documentation have been big parts of your practice too, Ti!any. How does Shu Lea’s story resonate with you?

TIFFANY

Hugely. It’s also why I wrote about the Will Be Televised series, which is so interesting to me because it happens in 1989, this massively pivotal global year of the Cold War. I think that series shows new tensions emerging within geopolitics that have really peaked in the last twelve years since the Arab Spring, describing a new era of Cold War politics.

I partly grew up here in the United States, but I returned to Hong Kong in 2018. It’s like I had been under a spell of wanting to go back as an adult and work there. I had a day job, and I was also volunteering in the protests. I shot a lot of footage, but that didn’t end up becoming my own artwork or films.

I made a film called Never Rest/Unrest (2020), which I shot on my iPhone. Instead of showing the intense moments of violence—the kinds of images that circulated on the front pages of global newspapers—I felt, as an artist, that I had another role, something else to do, namely to document in a different way, beyond judicial evidence or journalistic reporting. Shu Lea, you don’t use the term “journalism,” right? You’re using terms like “media activism.” Also, it’s interesting how you’re always updating your practice to the technologies of the moment. I can’t help but think of the ways in which media technologies have shifted as the forms of activism themselves shifted to keep pace with the times.

SHU LEA

I’m very aware that the media landscape has changed alongside activism. Particularly with the Be Water movement in Hong Kong in 2019, and how Black Lives Matter became transnational by 2022. Media technology has affected how we conduct activism. I want to re"ect back on Electronic Disturbance in the 1990s, and online activism from Ricardo Dominguez and Critical Art Ensemble, to name just a few key players, and consider how 2024’s university occupy movement returns us to the physical and the analog (for instance setting up tents for sleeping in). Of course, with the current mobile technology, we are tracked and tracking, and our data become assets of profit- making corporations. The access/hacking of the technology accounts for devising the strategies and tactics.

LAUREN

I really appreciate this conversation on media activism. It has such a rich history, and it’s interesting to think about your involvement, Shu Lea.

Let’s move in a slightly different but related direction and talk about the body. There is such a strong alignment between your work and the theory of Paul B. Preciado, who curated 3x3x6, particularly around their term “pharmacopornographic capitalism,” 6 which describes, in their words, “the production of the sexual body and subjectivity within a new power regime dominated by bio, chemical, and internet communication technologies, where the traditional frontiers between natural and artificial, between inside and outside, between present and absent, between producer and receiver are blurring.” 7 This sounds so much like the landscapes and bodily blurs in your work, for instance in UKI, in which Reiko, a “defunct replicant,” tries to reconstitute themselves in a world—Etrashville—where the sinister company GENOM Co is taking human bodies and reengineering their red blood cells into nano-computers. Could you speak about how you picture the body in a work like UKI? Does it still have an en"eshed organic basis, or is it entirely encoded, or engineered, or somewhere in between, in a transitional state?

SHU LEA

In the early 1990s, the body, particularly in Those Fluttering Objects of Desire, where I invited sixteen female artists to use their bodies as contested ground, was very analog and very physical. The body was present. By 1998, with Brandon, the body existed with attached prostheses, the body as an apparatus. I uploaded Brandon Teena into cyberspace, where virtual encounters prompted the same cautions as in the real world. A$er Brandon, I.K.U. set out to reclaim the body as a medium, a tool, a vault in which the orgasm is data-fied, collectible, consumable, sellable under the corporate profit-making scheme. The 1990s proved porn was the winner on the internet. Yet we finally lost the internet, and we lost the body.

With UKI, I set out for a new cycle of work, Viral Love Biohack (2009–23) with a Hangar media lab residency in Barcelona. UKI is named for the virus generated in the plot, and how Reiko, the coder/replicant in I.K.U., would become. My focus switched to biotech, and bioengineering that had been developed in the bioscience field. With the development of cell culture, I didn’t consider the body as an entity anymore. Rather, it has been colonized, occupied by the corporations. We have forsaken prosthetic cyborg-bodies and become kin with microbes. We have departed from the gender binary and deviated into transgenic discourse. Finally in UKI, a defunct Reiko is taken over by the divine intervention of the virus.

LAUREN

It’s illuminating to hear you outline it as an evolution, as phases.

TIFFANY

And it’s so interesting to hear you talk about how we’ve lost the body and how we’ve lost the internet. I’ve read previously that Fresh Kill is connected to what you call the “dumping of garbage TV programs” in the Global South. 8 We’re living in a time of such an intense glut of industries, corporations, and even states making vast amounts of content. Some of that content isn’t even human-generated; it’s not “organically” produced in the digital sense of that word. It’s generated by AI or bot farms. As you work in these updated technologies, do you believe streaming technologies have broadened access to rare films and movies, or has something else happened? I’m also curious about this moment in which you’re returning to the cinema, taking your film on the road to art- house cinemas. Can you tell us about working in film and video through different distribution models?

SHU LEA

I’m not against streaming. It’s just a different mode of transmission and distribution. My desire to bring the film to the cinema remains, though. I think it’s a tremendous experience when everyone gathers in a cinema. For me, the screen gathers a collective body. It doesn’t matter how big the theater is—it’s about an audience looking at the same image and sensing it in different ways. For example, I’m about to embark on a road trip across the United States, showing Fresh Kill’s remastered 35mm print at art houses and independent cinemas where 35mm projection is still treasured. I’m traveling with two young filmmakers, Jean Paul Jones, based in Los Angeles, and Jazz Franklin, based in New Orleans. It has required a lot of coordination on my part, and still we cannot entirely prepare for the unknown factors. We have confirmed twenty cinemas, one stop being Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, which has seven hundred seats. My challenge will be to fill these seven hundred seats. Imagine the vibe for this collective experience! Seven hundred people breathing together, laughing together, or making culminations together. I had such aroused, uplifting sensations when Fresh Kill’s new 35mm print premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music last April. The audience went wild, cheering, laughing. The film spoke to them and they responded.

Coming back to the tension—being on the road, in the cinema, or logged on with one’s computer screen, the mobile phone, the pads—are we being entertained, interfaced, or socially mediated? How can we ever come to terms with how the grandeur of celluloid cinema degenerated into counting gigabytes per second?