The Gay Heyday of 1970s San Francisco

December 2019

These photos capture the gay heyday of 1970s San Francisco. It's an intimate chronicle of post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS life in the Castro.

Text by Mahoro Seward

“The Castro embodied all that was fun about the 1970s,” writes Hal Fischer, the auteur of Gay Semiotics(1977), one of the most significant visual relics of those halcyon days. “The election of Harvey Milk gave the community a tremendous sense of empowerment. The sexual revolution lived on, and social diseases, which were rampant, didn’t require much more than a trip to the city clinic and a course of antibiotics,” he continues. “Gay bathhouses, which would be closed down in the 1980s in an ineffective knee-jerk response to the AIDSepidemic, were plentiful and catered to a variety of tastes. At 2:00 a.m., when the bars closed, hundreds of men would flood out onto Eighteenth and Castro Streets. It was a playground and no one need go home alone.”

The words above are taken from ‘At the Center of the Gay Universe’, the closing essay of Hal Fischer: The Gay Seventies, a newly published monograph assembling Hal’s complete photo-text works, which he produced between 1977 and 1979, including Gay Semiotics: Hal’s witty documentary of gay archetypes and the intricate, visual codification of gay desire. Its chronological exhibition of the artist’s later works allow for a more robust appreciation of the artist’s contribution to both gay and wider, contemporary visual culture.

Parallel to the book’s launch, three of the works printed in its pages are currently exhibited at Project Native Informant in East London, their first time on show in the UK. “Throughout his work, Hal was really trying to capture a very specific community,” explains Stephan Tanbin Sastrawidjaja, the gallery’s founder. “It was a community that emerged post-Stonewall and pre-AIDS; the works document a very specific, concentrated period of time.”

Specific as the contexts it observes may be, the works still resonate today. “They feel particularly fresh in the political context that we’re currently living in,” Stephan says. “While there have been lots of advances regarding LGBTQI issues, particularly here in the UK, we’ve also seen an increase in reactionary fascistic actions. It’s good to be reminded of a similar period in time where, yes, it was quite liberated, but the reason why gay men had to express themselves through very specific, secret codes, was because they were not able to express themselves publicly. Doing so could potentially result in violence.”

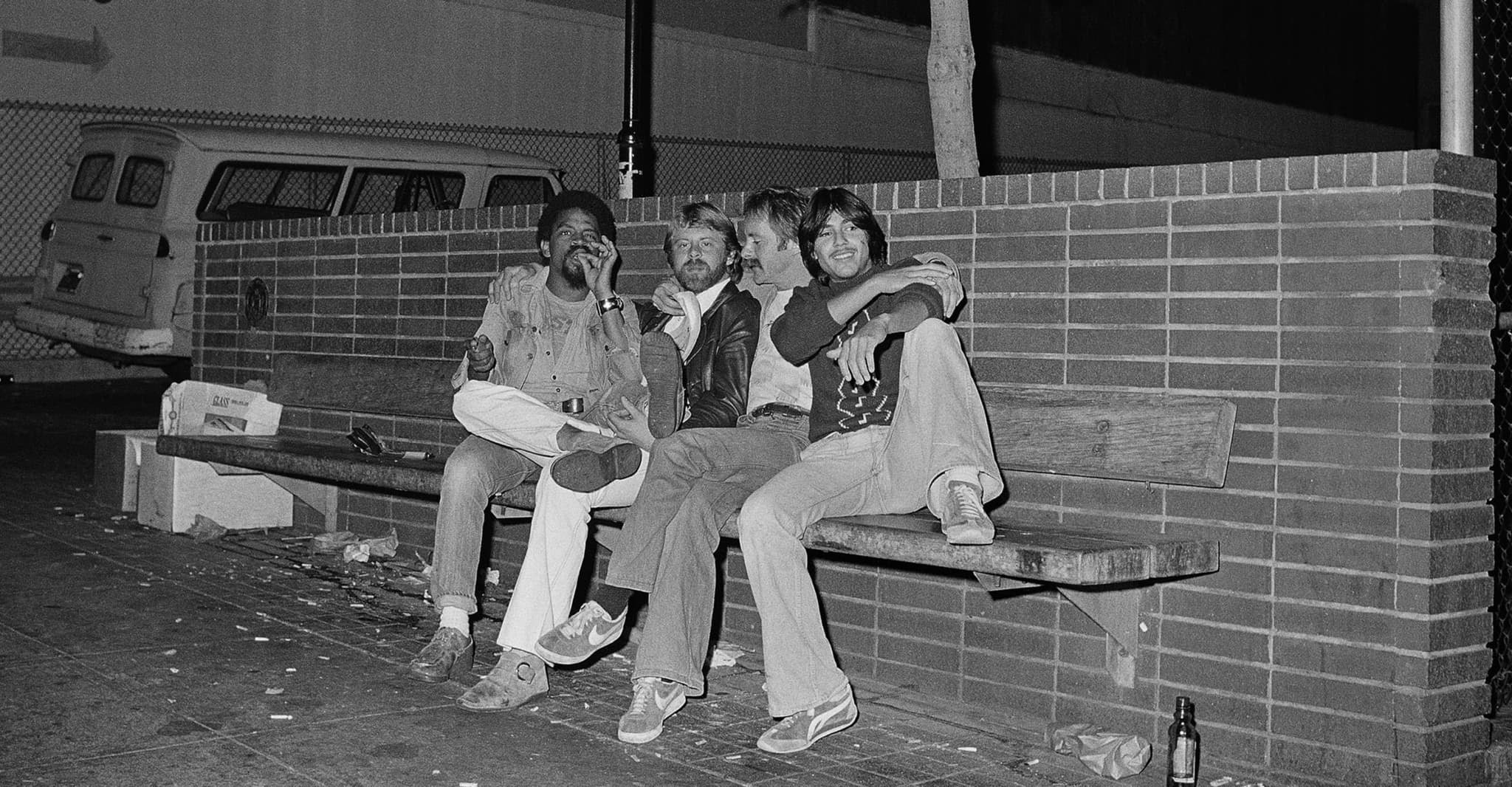

In 18th nr. Castro Street (1978), the enmeshing of San Francisco’s gay community with the Castro’s fabric of the city is captured across 24 stills, taken over as many hours at a bus stop at the district’s heart. As much a durational performance as it is a photographic chronicle, each image is accompanied by text that weaves back and forth between objective caption and narrative, filling in the moments that pass between each photo’s taking. “It really creates a sort of narrative as you walk through and read, a performative element, that draws you into his experience of going through each hour: trying to ward off hunger, or not leave early; cruising; getting a little high, taking a nap with someone he’s just picked up,” says Stephan.

“I embarked on Castro St. with a sense of how I would physically structure the piece, but no idea how the 24 hours would play out -- what the photos would present or the text reveal,” Hal writes via email. It’s perhaps how the images harbour that powerful sense of incidental authenticity. All the same, the intimacy both the pictures and text imply indicates something beyond a simple knack for capturing candid snaps. “Hal’s set up for the images was quite meticulous, and took some time. As such, the subjects are very aware that they’re having their picture taken,” explains Stephan. “Sometimes they perform for the camera, sometimes they ignore it, which is its own kind of performance. It’s interesting to think about the multiple ways of looking, these people looking at the camera, at us, and how we then look at that as well.” The result is an exhaustive ethnographic study of the community, but from the point of view of an insider. “His approach in Castro Streetis somewhat anthropological, but in his own native informant style. He is very much an insider, a part of the community, rather than an outsider looking in,” Stephan concludes.

Civic Center (1979) notably departs from the observational, deadpan humour that tinges Gay Semiotics and 18th nr. Castro Street, though it maintains the “absence of metaphor and deliberate neutrality that draws from advertising and commercial photography,” an common thread running through Hal's work of the period, he says. Here, this surface neutrality colours a triptych of identical shots of San Francisco’s imposing City Hall, each accompanied by text recounting a key moment in the city’s gay history: the 1978 Pride celebration, a protest against Proposition 6, which would have banned gays from working in Californian schools, and the assassination of Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay elected official.

“Civic Center is a response to November 1978, one of the most traumatic months in San Francisco history,” Hal explains. “I used the same image in all three juxtapositions, in effect making City Hall and Civic Center plaza into something unchanging or monolithic. Perhaps it was me thinking that the monumentality of City Hall (it’s an oversized building in a beaux-arts style) rendered whatever happened in the plaza in front of it, whatever might be different from one event to another, visually nonessential.” And indeed, a sense of the unyielding permanence and scale of institutional power dominates. But here, the accompanying texts, sobering accounts of the gradual decline of the relationship between the city’s gay community and its bureaucracy, convey a the former's inability to freely thrive within the latter's remit. ”The controlling powers don’t want to see the media project a gay image via nudity or drag,” writes Hal below the first image of the series, referring to the aforementioned pride celebration. As such “the flamboyant excesses of past parades” are quelled. In light of the sobering retrospect that the AIDS crisis offers, it’s hard not to view the series as an eerily prescient snapshot of an epoch in decline, of an empire’s imminent eclipse.

Offering an ostensibly lighter insight into late 70s San Francisco is Cheap Chic Homo (1979), a dissection of a friend’s outfit, an exemplary of uniquely San Franciscan dress sensibility. Known for its wildly unpredictable weather, light layering was the favoured tactic of the city’s denizens. As such, the series comprises five images of Steven in gradual states of undress, frequently with a suggestive smirk on his face, as if he were performing a coy strip-tease, or starring in a wink-wink campaign for The Gap. The blank humour of the works, however, is dashed with a subtle consumerist critique. Prefacing Cheap Chic Homo is a list of the items Stephen wears, accompanied with each piece’s price and provenance, commodifying his creatively assembled outfit, and its wearer by default. “I find it quite prescient when we're talking about consumerism, and the way in which the work, in a slightly brutal but also humorous way really breaks down not only what the garments are, but where it was acquired, how much it cost. It's a very prescient institutional critique, where he's sensing the consumerism that's about to happen,” says Stephan.

Then again, there’s also an undeniable sense of fun. Hal’s work, ultimately, is a loving tribute to his San Francisco, a city in which “Oscar Wilde would have found all the delights he envisioned in the next world and more,” he writes in the book’s closing essay. “It was great to be gay, and the Castro was the epicentre of the gay universe.”