SWEET SUBVERSIONS: DIS Curate The Biennale de L'Image en Mouvement, Geneva

September 2021

The 17th edition of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement at the Centre d’Art Contemporain de Genève is a tightly packaged proposal for short-circuiting familiar narratives.Titled A Goodbye Letter, A Love Call, A Wake-Up Song and curated by the New York-based art collective DIS with the center’s director Andrea Bellini, the video-based exhibition spreads over the Kunsthalle’s three floors, and in addition includes two off-site works installed at train stations, part of a larger project bringing contemporary art to the region’s commuter rail network.

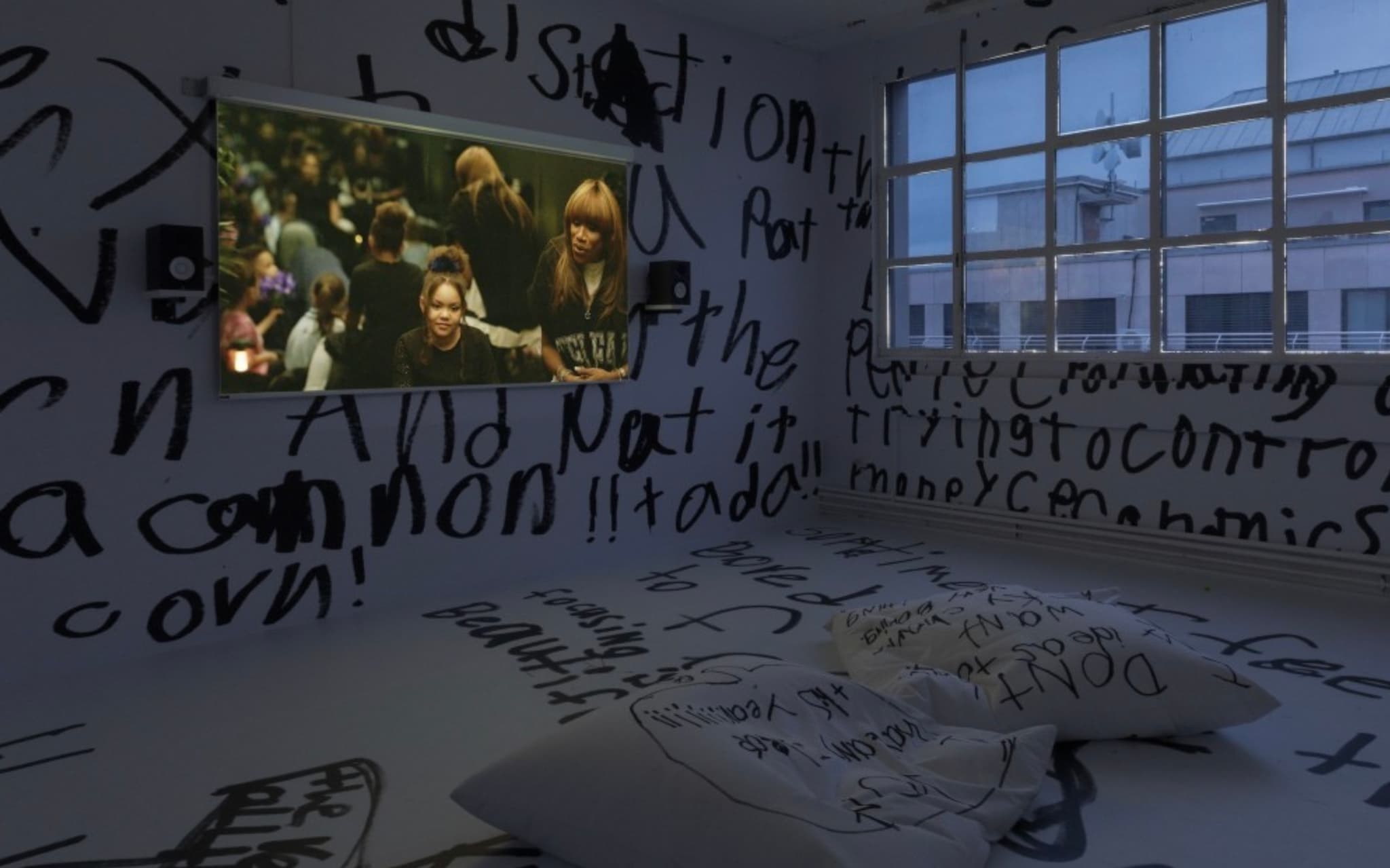

Each video at the Kunsthalle is relegated to its own room, behind doors with porthole windows that permit some flashing hints of what’s in store once you enter. No room has the same scenography — one features courtroom pews, another a two-way-mirror suggesting an interrogation room. DIS co-founder Lauren Boyle explains that this exhibition design was conceived to create a “hotel room vibe.” The collective and Bellini’s design also features sculptural lights by the fraternal duo GRAU, large, pill-shaped bulbs glowing orange, red, and blue, looking not unlike oversized LEDs, perhaps like those that light our screens. Their preternatural incandescence suffuses the halls, creating an otherworldliness, a sense of a light at the end of the tunnel always lurking, and unifies the sprawling space, formerly a scientific instruments factory. The exhibition’s text proposes that while the biennale’s “previous edition was dedicated to the idea of going beyond the screen, BIM’21 explores the exact opposite: a moving image that can exist both in physical space and on digital screens.” But in a way, one is stepping into the screen, into a sort of streaming service explore page made physical. These halls, these spaces between: they’re the spaces where choices are made; they’re the spaces where things refuse to resolve, where the distance between fiction and reality, between pre-recorded and lived, blurs.

Each work in the show was commissioned for the biennial. The majority feature the high-production values and sleek aesthetic that DIS first became known for, their earliest projects, including an online magazine and a stock image catalogue, pioneering a mode of critiquing corporate marketing by subverting its language. (One could argue that the collective precipitated a hyper self-conscious style of advertising that’s become more and more popular the past several years, with brands like Balenciaga leading the way, a phenomenon critic Taylore Scarabelli recently called on Twitter the “dis-ification of mainstream media.”) With A Goodbye Letter, A Love Call, A Wake-Up Song the collective takes back this mode of production, building on the work they’ve done over recent years through their streaming platform dis.art, which features collaborations with filmmakers, artists, and theorists to create what they’ve dubbed “edutainment.”

The work in the biennial ranges from the explicitly didactic to the more abstract. At one end of the spectrum is artist and educator Mandy Harris Williams’s Couture Critiques, which blends an Edward Saïd lecture with the cinematic stylings of 90s-era MTV to construct a tightly wound meditation on the role and relevance of the “intellectual.” The show is self-conscious, with Williams asking about the (ir)responsibility of her accepting and using money to make the show itself. By posing questions within and outside the show’s frames, various material layers of implication are thrust onto the viewer.

Also engaging pop-culture filmic tropes to new ends is artist Sabrina Röthlisberger Belkacem’s Santa Sangre, a suite of music videos, inviting the viewer into a world of ruins and fairytales, where mysticism and transformative potential reign. There are woodland scenes; there’s champagne in a hot tub; there’s a stabbing. It all makes sense, I swear.

Other familiar forms appear: Artist and designer Akeem Smith intercuts found footage of dancehall parties with news media and cartoons from his childhood; multimedia artist Camille Henrot’s meditation on the outward expressions of inner lives (spirituality, surgery, digestion) is plastered with news chyrons; writers and actors Emily Allan and Leah Hennessey’s highly narrative, mock-serious comedy Byron & Shelley: Illuminati Detectivesfeels not unlike a period TV show, albeit even more unhinged and introducing themes of poetics, class, and surveillance; DIS describes their own contribution, a video authored by the collective’s founders, Everything but the World, as departing from the idea of a non-linear natural history show.

The (linguistic) construction of our sense of the real, the boundaries between human and not, natural and cultural, are interrogated through various lenses in the exhibition, perhaps most lucidly in Penumbra, a collaboration between artists Julianna Huxtable and Hannah Black and the creative studio And Or Forever. In the 3D-rendered world they bring to life, domesticated animals — those that are in the murky middle ground of acculturated and “wild” — are jurors for cases brought against creatures like pangolins and octopuses. Referencing the real history of animal trials, the discursive project confronts the boundaries that define culture and troubles the law’s impact on physical being.

Images, image making, and streaming itself are also frequent subjects of the works. “Cameras don’t take sides,” claims a uniformed instructor in Theo Anthony’s real-time, three-channel video Neutral Witness, which presents a Baltimore Police Department body-camera training session in full, and which was among the elements of his recent award-winning feature All Light, Everywhere. When enumerating the body-cam’s purposes, the instructor notes “accountability” as a chief reason. “Everyone’s actions are captured on camera though, so not only is it accountability for us, but it’s accountability for those that we deal with.” This doesn’t stop him though from asking Anthony to shut off his cameras when the trainees watch a video of a pursuit where a man is shot at. The audio is running — the cops in the classroom can be heard laughing, mocking. By presenting the class from different angles but in its full, uncut duration, Neutral Witness works as a counter-film to the body-cam footage, a documentary of how documentation is never neutral.

On five monitors and a projection, one room streams ever-evolving selections from TELFAR TV — the fashion brand’s new project, a 24-hour channel which Boyle compares to a QVC-style network. Designed to be filled by user-made content, the brand describes it as “an experiment in the UN-OWNED aka UNKNOWN aka FREE.” Whereas media services provide pre-ordained content, TELFAR TV requires the public to make their own, an image of empowerment as much as an emulation of today’s social media platforms that turn us all into “creators” to line other’s pockets. (An ironic aside: Telfar Clemens has been going out wearing “spy glasses,” perhaps a form of sousveillance.)

In combining the strategies of cinema, educational television, and experimental video art, the commissions in the biennial evoke the ideas of the New Narrative writers, who sought to reconcile the abstraction of Language poetry with the lived experiences of gay and working-class subjects by melding avant-garde writing, narrative fiction, pornography, critical theory, and gossip. As Robert Glück, one of its key figures, wrote of the movement’s origins, “I read and wrote to invoke what seemed impossible — relation itself — in order to take part in a world that ceaselessly makes itself up, to ‘wake up’ to the world, to recognize the world, to be convinced that the world exists, to take revenge on the world for not existing.” In this sense, A Goodbye Letter, A Love Call, A Wake-Up Song, is propaganda for the possible, an enjoinder to be present for the anti-present. The indulgence of recognizable, commodified forms does not negate the content, but rather adds not only a plane of access, but a plane of useful confusion. As Bruce Boone, another New Narrative writer, wrote, “When evaluating image in American culture, isn’t it a commodity whether anyone likes it or not? You make your additions and subtractions from that point on.” That describes not cynical resignation to familiar forms, but rather a commitment to leveraging and expanding form’s potential.

GRAU’s sculptures, Fire, reference the originary control of light. While humans taming fire anticipated the screen image, it also stands as a sort of boundary line in the slow march towards the invention of history. As Prometheus’s incendiary theft of fire from the gods is the mythic tale of society’s origin, the invocation of fire here serves a launching point to conceive not only how history happened, but how “history” is made up, and in service of what or whom. This exhibition, its curators say, presents a “need to debunk narratives” while offering in their place methods for imagining different stories, and thus different ways of being. It “challenge(s) the notion that this is the only possible world and the only possible economic system, a concept of history that has long suppressed political and cultural debate.” It reminds me of a quote from Candide, Voltaire’s 1759 satire of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s delusional defense and acceptance of evil’s persistence despite his God’s purported benevolence: “If this is the best of possible worlds, what then are the others?” In DIS’s microcosmic streaming universe this question is flipped on its head. We are presented not fantasy, but possibility, a hope for making better worlds.

By Drew Zeiba