Shu Lea Cheang: Scifi New Queer Cinema, 1994-2023

April 2024

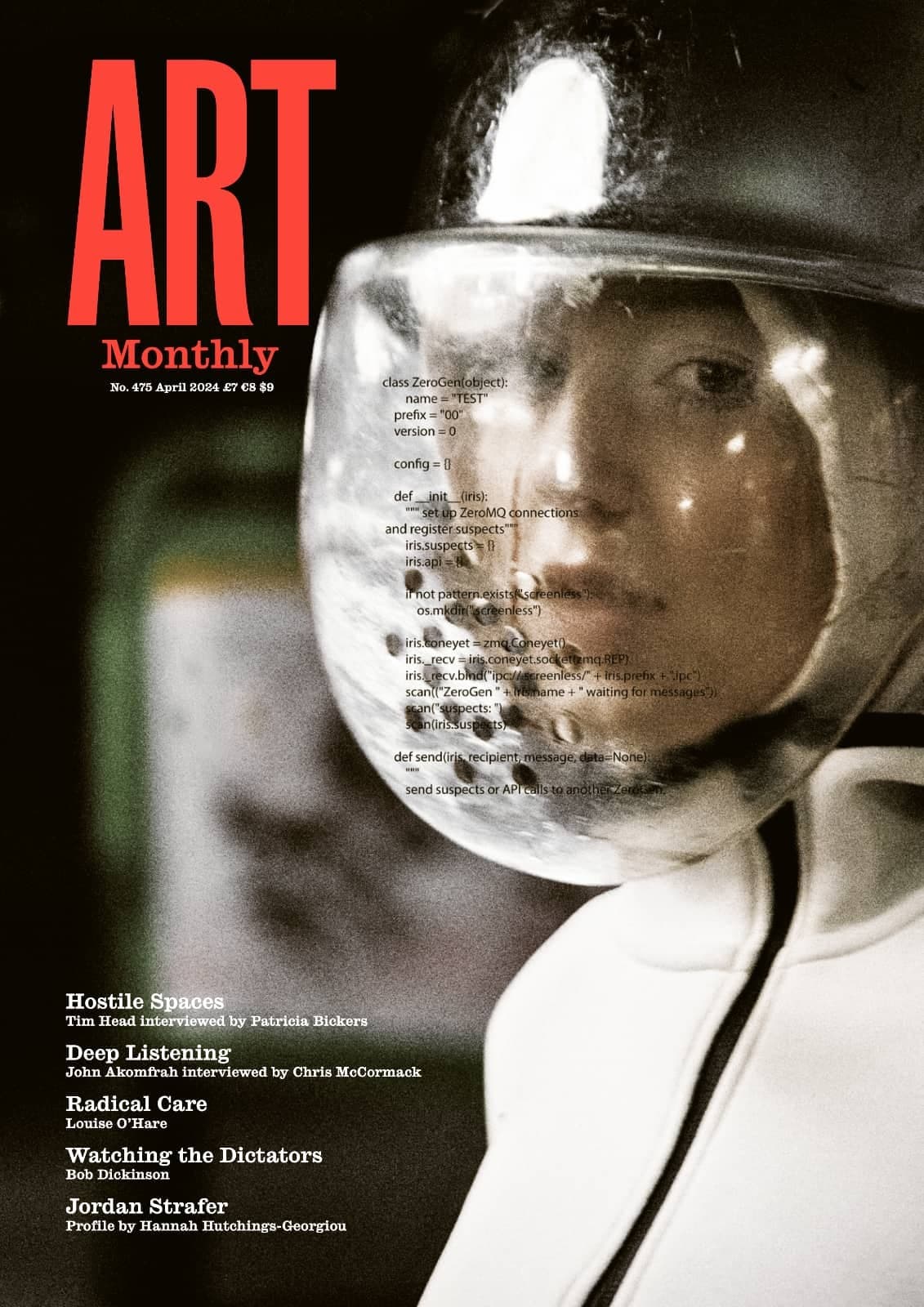

'Early in the 21st Century, announces text at the start of I.K.U., 'the Genom Corporation advanced the sexual revolution' by deploying a squad of humanoid robots to sleep with as many people as possible and collect their orgasm data. Over the next 90 minutes we follow feminine 'data hunters' on their 'non-stop sexing journey' through the 'night-world' of New Tokyo. One insatiable robot awaits her prey in an inflatable pink enclosure, while a shibari master ties a woman up and lowers her in like a mouse into a snake tank. Another so-called 'I.K.U. Coder' uses a less elaborate tactic, seducing victims next to a fish tank in a sushi restaurant.

The film, released in 2000, is subtitled "This is not love. This is sex' and unsurprisingly the 'hunters' are not especially affectionate: they murmur phrases like 'I want it very much' in a stilted, servile voice, their groans and slurps out of sync with the on-screen action. As each scene comes to an end, the robot's arm morphs into a dildo which, witnessed via cavity-view animation, extracts precious data from inside the climaxing partner. Welcome to the cinematic cyber-carnival of Shu Lea Chang, whose four feature-length films are currently showing on a weekly schedule in a dark, carpeted room at London's Project Native Informant.

In conventional pornography (as well as much classical film), the male subject dominates the female object, the narrative and camerawork defined by his desire. Here, however, the ostensibly female figure oscillates between cutesy anime-style sex object and penetrative predator, weaponising her erotic appeal as her dainty arms become extractive dildos. In Cheang's 2017 film Fluido, semen is sold as a powerful narcotic: much of the film is taken up with relentless wanking on the part of "bio-drug carriers' Ejaculation - normally the cathartic finale in porn - is here instrumentalised and animation, enforced to the point of mundanity. Scenes from the production line are contrasted with orgiastic celebrations of queer desire. 'Let there be pleasure on earth and 'let it begin with me', proclaims a masturbating character dubbed 'The Pornoterrorist'. With wit and bravery, Cheang rejects the heteronormative structures most pornography bluntly asserts.

The Genom Corporation reappears in her 2023 film UKI offering a service whereby people can sign up online in order to immediately orgasm when they touch hands with other users. One pair meet at a bar modelled on Edward Hopper's Nighthawks, 1942. 'I want to really meet you, a woman says in a rare moment of sincerity, to which her acquaintance replies 'my desire to engage with you is purely an act of data transaction. Meanwhile, a suited figure reads the news - the government encouraging women to reproduce and limiting the right to abortion - but the pair are distracted palms touching, eyes closed, and breathing heavily across the bar. This is orgasm as 'opium of the masses'. Why engage with society when solipsistic pleasure is so intense and so easy? During their 'transaction' Genom collects 'genetic information' which is sold on to 'therapeutic companies'

Cheang's work emerges from the late-20th-century hope that technology might offer escape from patriarchal oppression and the biological essentialism that fuels misogyny. Donna Haraway famously envisaged the cyborg as a hybrid figure that dissolves the hierarchical divisions found between human-non-human and man-woman as a way to challenge the core tenets of capitalist society. Manufactured not born, the cyborg undermines the bourgeois family's reproductive func-tion. UKI stages a conflict between tech's emancipatory potential and social tradition. Genom's handshake orgasms untether sexual pleasure from penetration, desire from power, and gradually generate 'hormonal and physiological androgyny" in users. The government responds by incentivising women to return to their role as birth-giving machine[s]*

Cheang's films are themselves cyborg creations glitching into existence, recalcitrant and inventive, and constantly blurring the lines between culture and nature. Her first feature, Fresh Kill, 1994, takes place in the shadow of a landfill site which, it is hoped, will become a mountain park. People fish through drains for scraps of 'technotrash", a man brushes 'bird excrement' off' satellite dishes, and a girl falls ill with a disease caused by industrial waste in the fod chain. These are ecosystem dramas in which technology and biology are always intermingled, in which human action is secondary to the movement of fluids, viruses and data.

Rather than simply illustrating this vision of total connection (by now the stuff of eco-critical cliché), the films satirise the way dreams of dissolved boundaries and tradition-smashing technology have been co-opted. Freedom and the free market have become confused when a corporation claims to have 'advanced the sexual revolution' Chang brings to queer culture a lesson learnt from sci-fi: technology is as apocalyptic as it is messianic, it augments rather than weakens mechanisms of domination. In this respect, her work evokes the dizzying complexity of contemporary activism which is forced to operate in the cracks between governments and companies, old systems of repression and novel modes of surveillance and control.

By Michael Kurtz