SHOPKEEPERS OF THE WORLD UNITE: Christopher Glazek on Generation DIS

June 2014

One evening last summer, far from New York City, I was cornered by a senior curator from a prestigious arts institution. The woman, who was urbane, stylish, and in her late thirties, had a pressing question. “You live in Los Angeles,” she noted. “Can you tell me, is Petra Cortright a feminist?”

I squirmed as I considered how to avoid falling into this trap. I was acquainted with Cortright, a Santa Barbara–raised artist known for her YouTube clips and desktop-stripper animations, but I didn’t know much about her politics. Smelling weakness, the senior curator pressed on: “What about Amalia Ulman?”—the twenty-five-year-old transatlantic wanderer known for video shorts about commerce and coming of age—“Do these girls know anything about Marxism or feminist theory?” Cortright and Ulman are often described as “post-Internet” artists, a debated term that roughly describes those whose work both addresses and bears the influence of social media. I had no special access to their reading habits; it was true that in our conversations Marx had never come up.

“I’m not sure they would find those vocabularies to be the most revealing tools for discussing their work,” I stuttered. The curator leaned in to register her dismay with an entire cohort. “What is happening with these twenty-something artists? These people surrounding DISmagazine? Do they really just worship consumerism? And Instagram? Am I missing something?”

She was, and she wasn’t. “Instagram,” which the curator seemed to be using as an umbrella term for the entire social Web, was definitely having an impact on the generation of artists with whom I had grown up. So was DIS, an arch and futuristic media platform devoted to the Internet, art, and fashion. In spite of its recent vintage and shoestring budget, DIS, whose content ranged from critical essays and runway reviews to DJ mixes and video collages, was arguably as influential among art-school grads as any number of its more established rivals.

As the curator was herself a Marxist, I was tempted to suggest a Marxist alibi for the emerging generation’s consumer antics. Had I pursued that tack, I would have cited “accelerationism,” an ideology associated with the cybernetic philosopher Nick Land. As curator Agatha Wara, a DISassociate, once explained it to me, accelerationists believe that “the only way to get over capital is through capital”—that is, by accelerating capitalism’s own tendency toward self-destruction. (The roots of accelerationism extend back to Marx himself, who once wrote that he supported free trade because he believed it would encourage revolution.) I doubted, though, that grunting “accelerationism” would tame the incredulous curator. It sounded like an ex post facto rationalization, in part because it was: My own artist friends, I was fairly certain, had not embraced consumerism as part of a long game in the ultimate struggle to destroy capitalism. “What I think you don’t understand,” I replied, “is that these people really don’t like school.”

By “school” I didn’t mean literal matriculation—many of the artists I knew enjoyed whatever years they spent under the formal tutelage of credentialed elders. Very few, though, had found their operational armature in academic theory. This wasn’t just a trend among visual artists—in the age of Wikipedia, the ability to manipulate specialized vocabularies and esoteric knowledge was commanding less and less authority across the board, from Marxism to indie music. The easy diffusion of information was having ripple effects across publishing, art, and the avant-garde.

This was clear to many students, but not always to their professors, who understandably continued to ply the methods and methodologies that had helped them get tenure. As a result, many art-school grads were coming of age at a time when what felt most oppressive wasn’t consumer capitalism: It was the institutional codes and guild vocabularies in which they had been trained.

Part of this reorientation was driven by technological innovation, but another part was prompted by economic collapse and credentialist backlash. Just as the economy was sputtering, MFA programs were becoming de rigueur, normalizing debt-financed degree acquisition at precisely the time when a degree could no longer guarantee a stable income (or at least not one large enough to repay student loans). For an emerging crop of Insta-queers, lonely girls, and slacker bros, the market—especially the digital marketplace, with its emphasis on clarity, preening subjectivity, and infinite accessibility—suggested an alternative to the onerous grant applications and bureaucratic ring-kissing that drove the art-academic complex. Weary of the rigorless ramblings of adjuncts, many art-school grads found themselves inspired by hot designers and dropout entrepreneurs. It wasn’t hard to see how these figures more readily suggested the cowboy ethos of the creative outlaw than did traditional artists, who came freighted with a “transgressive” framework that often eluded actual transgression.

The curator wasn’t buying it. To her, it all looked like craven capitulation.

I recently advised some friends on naming a new branding agency. They wanted to call it Hypergeist, which I liked. “Very ghost in the machine,” I observed. “Sort of techno-goth, zeitgeist-gone-wild.” The question was how to describe the agency. They wanted to call it a “creative studio,” which I didn’t like. “‘Creative studio’ sounds small and aggravating,” I observed. “It’s like calling it an atelier.” I was afraid they’d sound like hermits scrivening in a garret. As a counter, I suggested they make it plural: Hypergeist Creative Studios. “That way you sound big, like a production company—like an amusement park!” If sounding contemporary was the goal, I argued, the vibe to cultivate was industrial and collaborative. “Leave the medieval blacksmith thing to the craft breweries.” Being a craftsman hadn’t been cool since 2006. Embracing the postartisanal, procommercial turn was an important part of claiming membership in the rising contingent of tastemakers.

Around the same time that I was urging my friends to adopt the syntax of an amusement park, I started receiving press releases for “DISown,” an “art exhibition posing as a retail store” produced by DIS at Red Bull Studios. Reading the show’s list of featured artists was a bit uncanny: The roster was an eerily exact class photo, not only of people I had grown up with and partied alongside in New York (K-Hole, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Analisa Teachworth, Telfar, Maja Cule, Cyril Duval, Leilah Weinraub, Dora Budor) but also in Berlin (Daniel Keller, Simon Fujiwara, Timur Si-Qin) and Los Angeles (Lizzie Fitch, Ryan Trecartin, Amalia Ulman). The list seemed algorithmically assembled, as if Facebook had searched my timeline and created a customized exhibition based on my likes and interests. I knew all these people, but I hadn’t previously realized they all formed part of the same global alliance.

“DISown,” the show, was clearly a moment of culmination for DIS, the magazine. Although DIShad shown at fairs and galleries, its cultural ambitions had always been too broad for the gallery format. The opening of a “store” (however temporary) on Eighteenth Street with a Red Bull–sized budget seemed like a consequential step. Securing a retail revenue stream had long been a Holy Grail for the magazine; though not a nonprofit, DIS was widely believed to be nonprofitable. Until “DISown,” it seemed that DIS might have abandoned the retail goal, as most of its editors had started working for VFiles. VFiles was like DIS minus art plus commerce—a mainstream-facing media company that sold designer streetwear online and through a storefront in SoHo.

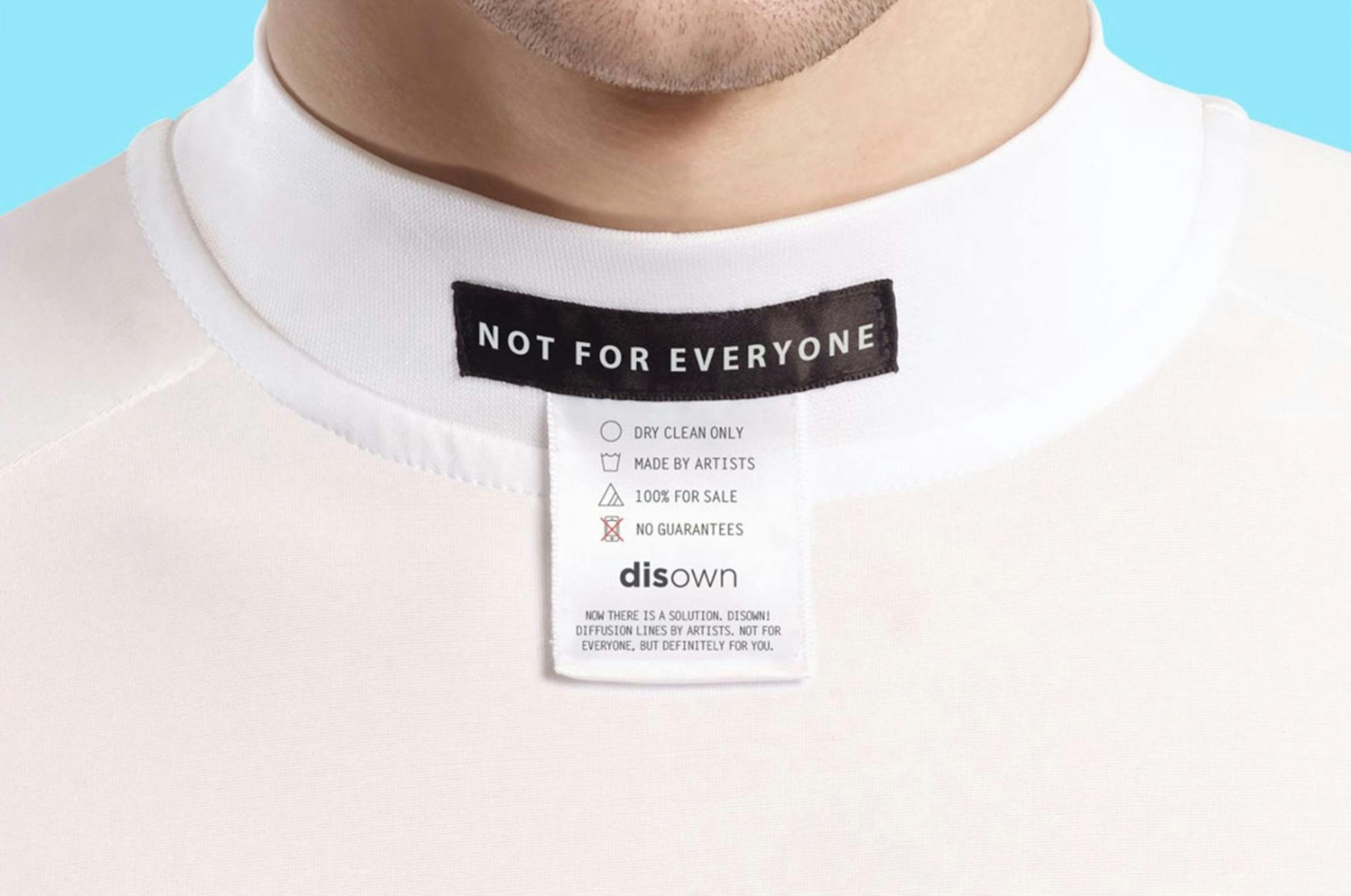

Eventually I made a pilgrimage to “DISown.” As soon as I walked in, I felt soothed; everything was sheathed in white, as in an Apple store or the Celestial Room at a Mormon temple. On the floor were bizarre, drunken-looking directional markers, Lizzie Fitch’s homage to the floor plan of IKEA; there were also IKEA-inspired laundry bags for sale printed with the DIS logo. At the entrance, I was greeted with a blown-up version of the show’s flyer—a photo of a boy with an uncomfortably sexy smile, cut off at the eyes, wearing a white, inside-out mock-neck whose exposed tag, appropriately enough, displayed the exhibition’s tagline: NOT FOR EVERYONE. On a wall across the room, the same image, even larger, had been superimposed on a rock-climbing wall whose purpose seemed to be to provide a backdrop for event photos.

A variety of “consumer products” by contemporary artists and designers had been placed throughout the showroom. About half the offerings were clothing items—denim printed with a flame pattern from Korakrit’s new show at MoMA PS1; a sweatshirt by Trecartin with a graphic from his recent film Center Jenny; a baseball cap with a hidden spy cam by Keller; planter-cozy beanies by the art collective Jogging, emblazoned with the names of resistance heroes of the national-security era (Manning, Snowden, Assange, a misspelled Daniel Ellsberg). The other half were home furnishings—body pillows by Jon Rafman printed with photos of Emma Watson from different stages in her career; a beanbag by Bjarne Melgaard; a salad bowl by designers Hood by Air; a doormat by Budor covered in logos from electronics manufacturers, meant to evoke the practice, once common in Eastern Europe, of covering the floor during winter with deconstructed cardboard boxes to protect it from the snow. Objects ranged in price from $10 for the DIS IKEA bag to $4,800 for a luxury flotation device by Annika Kuhlmann and Christopher Kulendran Thomas.

Many of the items, including a giant hammock by Fitch and an underwear set by Ulman, were unique or handmade but designed to look mass-produced. Though the objects projected an aura, it was one of tribal affiliation—some call it “branding”—rather than of the Kantian sublime. If traditional artists struggle to maintain the fiction that holy artifacts emerge fully formed from their brains, the artists in “DISown” were more likely to pretend that they had used a fabricator when in fact they had done everything themselves. As with handcrafted techno beats, the “DISown” pieces strove to convey automation. (This is refreshing at a time when craftsmanship has been conceptually co-opted by the food industry. It may not be clear to anyone exactly what art is supposed to be, but it’s reasonably clear that it’s different from an heirloom tomato or a heritage turkey.)

“DISown”’s upfront commercialism served then to rebuke artists—including some who participated in the show itself—whose market value relies on presenting their work as somehow outside the market system. “DISown” thereby issued a critique, not of mass commercialism, but of the hypocrisy of the market’s marketable pretense of art for art’s sake. Large corporations underwrite museum exhibitions all the time: The difference with “DISown” was that it highlighted Red Bull’s involvement instead of concealing it. The result, the show wanted us to believe, was aura without the hypocrisy.

Many of the objects were individually fascinating; others seemed rushed or dutiful. But the show’s magic lay, not in the individual pieces, but in the way it branded its participants. By bringing together so many emerging artists from New York’s post-Internet scene and combining them with blue-chip favorites such as Melgaard, Trecartin, and Fujiwara, the show staked a powerful claim: DIS magazine, which began as an email exchange among twenty-odd friends, now stood for an entire generation.

Or at least part of a generation. In a promotional trailer made to accompany the show, Kelly Richards, a “DIS spokeswoman,” explained that while “DISown” is “not for everyone,” it is “definitely for you.” This was simultaneously a joke about the alchemy of branding—our product is only for special people, but also for everyone, because all consumers are special—and also a statement of fact: If you were watching this video, then “DISown” was definitely for you, because DIS, which describes itself as an “international community of writers, photographers, musicians, and DJs,” is really a social network that disseminates content to anyone who hits “follow.” No secret passwords necessary—if you click, you’re in.

What DIS had discovered—but what much of the art world still didn’t know—was that exclusivity had become obsolete. “Cool” wasn’t cool—the old downtown underground had lost its appeal. The goal was no longer to subvert the mainstream, but to refashion it in subversion’s own image. To be sure, DIS’s impact was more to rebrand cool rather than to actually obliterate social and aesthetic hierarchies, but its rebranding was not without worldly consequence. On the heels of a downtown era defined by Ryan McGinley’s vampire sidekicks and Purple’s aging pornographers, the culture propelled by DIS and affiliated parties like GHE20G0TH1K felt like a life-affirming, gender-fluid, multiracial utopia—the legatee, in some ways, of earlier art-music-nightlife moments, from disco to the Club Kids, but filtered through the Internet era’s more expansive potential for commingling.

Accessibility, or at least the veneer of accessibility, was the order of the day. DIS wasn’t for everyone, but it was definitely for me.

One day in the summer of 2010, I was staring at a computer screen in the Condé Nast citadel at 4 Times Square. The economy had barely recovered from its 2008 flameout, and the vibe in the building was glum: A few months back, Ruth Reichl’s Gourmet had shuttered, along with two wedding magazines and a parenting publication called Cookie. I was working as a fact-checker at the New Yorker and felt lucky to have the job. On this particular afternoon, while struggling via email to appease one of the magazine’s infamous egos, I noticed a link in my news feed to a post titled “Shoulder Dysmorphia.” I clicked through.

“It is no small secret,” the feature’s intro declared,

that an elite handful of homosexual men are responsible for the self-esteem of millions of women worldwide. The ever-expanding exacerbation of shoulder silhouettes in women's ready-to-wear will not only continue on its grotesque path into the grim future, but consumer anxieties over natural shoulder inadequacy will skyrocket, forcing women to undergo startling new surgical procedures, season to season, in order to keep up with the newest designer shapes.

Beside the text was a clickable arrow that took you through a fantastical photo shoot of malformed models, the apparent victims of imaginary surgeries to sharpen and extend their frames. The models’ shoulders were sculpted into extravagant designs—concave curves, elaborate ruffles—which matched silhouettes from actual garments by Rick Owens, Givenchy, and Lanvin.

Despite its formal modesty, “Shoulder Dysmorphia” felt profound: With ruthless economy, it had pegged a phenomenon (feeling bad about one’s shoulders), positioned it within a field of power (a world in thrall to gay fashion-house directors), and amplified it to its unnerving extreme (surgery). Was this satire? Prognostication? I couldn’t really tell. It reminded me a bit of the “political surrealism” that undergirded many of the more popular essays published by n+1, where I moonlighted as an editor. Unlike the n+1 pieces, though, the ideological commitments of “Shoulder Dysmorphia” were ambiguous. Were we supposed to revile the coming era of shoulder intensification or embrace it?

Surely, “Shoulder Dysmorphia” was something different from mere critique. It felt participatory, a cultural intervention that moved the needle—though in what direction I wasn’t sure. Instead of the standard pile of inert text and undermotivated imagery, it felt like a precision strike, both on my individual unconscious (I personally suffered from shoulder dysmorphia) and on the wider culture. With magazines tanking and galleries getting boarded up everywhere we looked, who among us would survive without augmenting our shoulder-to-waist ratios? I wondered at the time where this strange publication came from, but it wasn’t until this past spring that I heard the origin myth.

In late 2009, a year after the crash, a group of friends working in various corners of New York’s culture industry saw their freelance work dry up. Suddenly, they had a lot of time on their hands, and the idea emerged through an email chain to start a digital magazine. “It was an interesting moment,” Lauren Boyle told me in a recent interview. “People were still afraid of tweeting too much! At that time, DAZED, ID, Interview—they weren’t picking up the people we were interested in. We started organizing the community a little bit.”

Lauren and her partner, Marco Roso, an artist who sidelined in advertising, would host big evening meetings at their house on Hooper Street in South Williamsburg. The meetings would mist into parties, and the parties would morph into photo shoots. Eventually, the meetings/parties/shoots were whittled down to a core group of seven, including, in addition to Roso and Boyle: Solomon Chase, who had been doing fashion styling for print and TV; David Toro, a research assistant and art handler; Nick Scholl, a web developer who for years served as the magazine’s webmaster; Patrik Sandberg, a writer; and Samuel Adrian Massey III, a product developer.

Four of the founding editors had attended art school and had chosen to live in New York City over pursuing traditional art careers. “If I had wanted to paint,” said Boyle, “I would have gone to Philadelphia or Baltimore or Berlin.” Roso, who was a bit older and had an established art practice, moved to New York from Spain after spending eight years burning through various artist residencies. “When I lived in Europe, my life was just linked to grants—one grant after another. You hit a point where you go through all the grants.” Not that Roso thought artists in America were much better off—they were dependent on the gallery system. In New York, though, you could find freelance work in fashion or advertising while pursuing art on the side.

The editors decided to organize as an LLC rather than as a nonprofit because they didn’t want to rely on donors or grant-giving bodies. Instead, they nursed the dream that some day their magazine would make money.

FIVE YEARS ON, the fulfillment of that hope might be on the horizon. A profitable DIS might not do much to hasten the demise of capitalism, but it could have a salutary effect on the art world. If we take the magazine at its word, part of the purpose of creating consumer-facing “diffusion lines” is to liberate emerging artists from hyper-rich collectors. While many take for granted the entanglement of the art world with the ultra-elite, there was a time not all that long ago when close association with the very wealthy was a source of embarrassment for respected artists. The promise of the diffusion line is that it could allow artists to trade an alliance with the .01 percent for an art practice supported by the middle class. The idea is that artists could become a little more like Red Bull, which makes its money from the masses.

(Red Bull has evidently done a good job of persuading people that it’s really a long-lost cousin of DIS. Throughout the run of “DISown,” I heard numerous artists repeat the line, without irony, that Red Bull is “actually a media company”—the energy drinks were just a side thing. Time and again, I had to explain that this wasn’t true: Red Bull was in fact a beverage company. Its support for “DISown” and other art initiatives was a branding project to help sell energy drinks—energy drinks were not a fake-out to help fund projects like “DISown.” Perhaps, in the distant future, viewers of the Red Bull Network will no longer remember that the company began as a distributor of caffeine and taurine, but as of now, Red Bull’s identity as a media company is largely science fiction.)

Cheerleading for the middle class is one thing; making money from it is something else. Many of the artists featured in “DISown” are already showing at elite galleries. DIS itself had a four-week solo show last year at Suzanne Geiss as well as prominent placement in a widely discussed exhibition, “ProBio,” at MoMA PS1. They have gallery representation in Paris. The risk for “DISown,” for which the Red Bull exhibition was only the launching pad, is that instead of creating an alternative funding stream for artists, it might simply allow the artists involved to peddle their wares to major collectors with greater buzz and authority.

When I interviewed DIS, they insisted they would meet with Bed Bath & Beyond next week if the company were interested in rolling out a DIS diffusion line. (It did not seem to figure in their calculus that Marty Eisenberg, a vice president of Bed Bath & Beyond, happens to be one of the world’s biggest collectors.) That would be the real test—both of DIS’s seriousness about reaching the middle class and of the middle class’s readiness to embrace DIS.

Generation DIS is what the Internet did to the avant-garde. While it will take years to sort out the consequences of the magazine’s market-oriented provocations, we can begin to formulate the stakes. If DIS gets subsumed by the blue-chip establishment, they’ll be remembered as a richer version of earlier scene-driven collectives like Art Club 2000. If they succeed in delivering art to the masses, they’ll have accomplished something no one saw coming—the rebranding of aura and the unmooring of the avant-garde from its lordly patrons. That could make them the most important artists of the decade.

- Christopher Glazek