Review: Morag Keil, Passive Aggressive at Eden Eden, Berlin

October 2016

It’s in your reach / Concentrate. It’s 2000 and Placebo releases the ballad “Passive Aggressive.” As the band’s lead singer Brian Molko once affirmed, the song may address either love or religion, or even both, somehow retracing the site of ambivalence akin to the personality disorder of the same name.

That kind of gray area sprawls into every lyric of Black Market Music (2000), the UK band’s third studio album, which was given by Paul Cooper from a well-known music magazine an amusing score of 2.4 out of 10. Not surprisingly, Cooper’s fierce review is concerned with Placebo’s aim to sell “androgynous product to teenagers titillated by the screaming parade of someone else’s bisexuality.” By no means convinced about the authenticity of Molko’s sexual orientation, nor about the band’s musical consistency, Cooper goes on to say that “solipsism and self-plagiarism are… the band’s most exercised skills.” 1

Some years later, it may be argued that those same vices of egotism and inauthenticity attributed to Placebo have been reabsorbed into a routine construction and performance of one’s own identity, especially through the practice of self-branding on social media. Indeed, even if it is displayed as unique and unitary, the self is always an assemblage, in terms of both its manifold coexistent personas and its constant biological (re)production. Here the motorbikes in Morag Keil’s latest video passive aggressive (2016) are likewise a fantasy for the ownership of a monolithic machismo, when they would rather be a collage of several different components and eventually produced in series.

The video opens with the title flickering across two horizontal stripes in white and lilac, slightly less annoying than those click-baiting ads one can find on the sides of some web pages. Shot with a hand camera, passive aggressive relentlessly scrutinizes about eleven motorbikes found in the street. The first is burgundy, and its pneumatic body is analyzed starting from the top box and then descending toward the arch between the seat and the back wheel, following the silver muffler, ending the movement where the clutch cover is, going after the gleaming side fairing all the way down until the subframe, ascending rapidly to the leather tank and to the handlebars, down again to the front wheel, and finally climbing sideways to the black seat. Then there is a cut in the take, and the next motorbike appears, ready to be acted upon.

Yet the gaze is affectless, as disengaged and blind as a handheld metal detector inspection, somehow activated for no other reason than a bodily presence. Indeed, for every time that Keil takes the camera close to a motorbike’s component, she never uses the zoom, to the point that when she pats down its orifices the image goes black. Except for a few cases where attention is given to the motorbikes’ logos or when the lens seems to sensually touch their surfaces, these movements compose a scheme that, more or less, could be applied to all the following machines. The latter’s portraits are punctuated by stock video clips and brief excerpts of cartoon-based TV commercials, which Keil chose for their deployment of cuteness for selling. The animated bears for Nutmeg (an online investment management service), the dancing flame for EDF Energy (a UK energy company), and the heteronormative nuclear family for Lloyds TSB (a bank with an insurance plan called “For the Journey”) are proxies designed to neutralize the harmful potentiality of the commercial messages they carry via a childlike, inoffensive aspect.

The video ends with the UK Big Brother’s trance intro. Just before, one could hear some people discussing food and sharing. From the press release, we understand that they are competitors at that reality show and that they are talking about how to manage the weekly amount of money to buy groceries. The argument exploded because instead of buying food together and then sharing it, they resolved to split the money and let each to decide what to buy. In such a game, where voyeurism is just the other side of the coin, the gamblers play on their twin roles as victims and torturers.

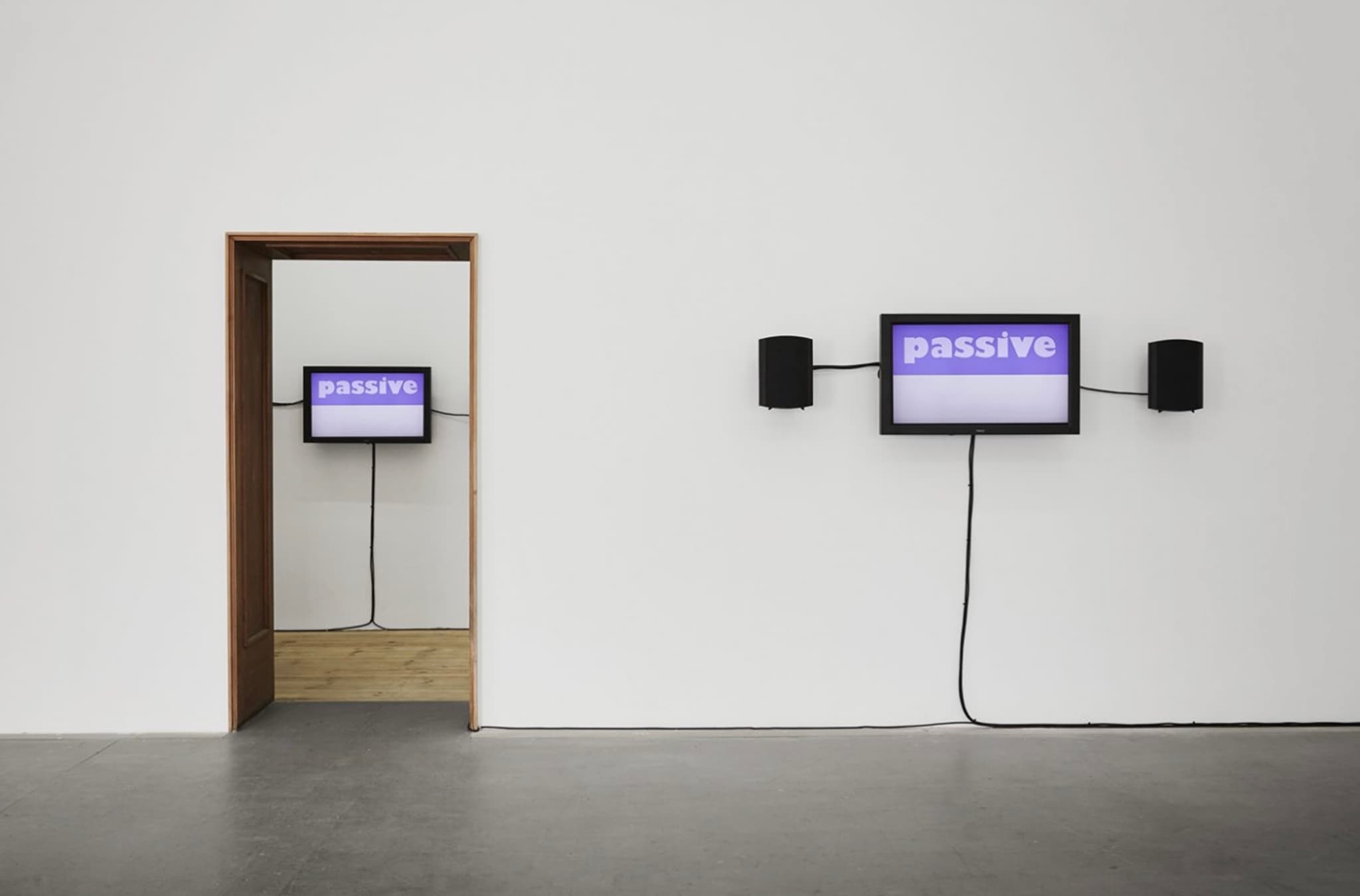

Experiencing passive aggressive feels natural as much as it seems to participate in a reality show—minus the redundancy of the apparatus: the video is broadcast in a synced loop on a screen in all of the six rooms at Eden Eden. Therefore, it may be sufficient to watch it once, and without leaving the entrance on the raised ground floor. Eventually one can even choose a favorite room according to their different sizes, lights, and temperatures: Is that entrance with wooden floors and whitewashed walls good? Better the longitudinal rectangle on the left or the latitudinal one on the right? An airy square, maybe? If fancying the basement, one can also find a humid and suffocating hallway or an insulated room with matchboard walls and light blue carpet, a mirror, and some shelves. The installation too is pretty simple and straightforward, for the screens share the same centerfold-like position in every room, being framed by a black speaker on each side and having black cables connecting them to a nearby socket. All these common characteristics appear to suggest a homogeneous experience of the space, through which one can navigate freely. Yet do they not begin to sound a little bit repetitive? Like, too much visible?

When considering the whole, it becomes evident that Morag Keil has structured the experience of the show and the work around the idea of a pervasive exposure. Out of the sneaky comfort and freedom of choice, one can realize that what is offered here is not a fluid experience, but rather a choreography of repeated gestures through it. Every screen is connected to the others via a circuit of cables, and they all share the same wall that traverses the two floors of the space. It could then be argued that this arrangement makes that wall a screen itself, an extended surface but also an ambiguous membrane, for it both screens Keil’s video—which is mainly shot outdoors—and screens the audience’s presence out of the passive aggressive show. If one follows this argument, the installation involves the preexisting architecture, the space acquires the quality of the backstage of a TV program—maybe a reality show—and the video is one of the episodes. Keil’s hand would be a jib camera operator and the viewer would just been following the camera ring.

Fascinatingly, the artist mimics here the mechanisms used to capture people and characters, gesture identities and desires, share a space, and form a community, even for a short time span. Aware of how the idea of a stable identity is “illusory and provisional”—as Alighiero Boetti defined the attempt to classify rivers—and how so-called Western societies still try to rely upon systems of inclusion and exclusion (as an example, the passive-aggressive behavior is categorized as a non-classifiable personality disorder), she attentively repositions the easy blame: from the people exposing themselves to make money under the capitalistic regimen of visibility to the infrastructure itself. Modulating her own identity-driven passive-aggressive paradigm, Morag Keil stages both terms by stretching them and embracing the newborn, gray, and troublesome in-between.