Profile | Hal Fischer

January 2020

Chris McCormack discusses the invention of languages by subcultures, and how intersect with the everyday, as revealed in the work of the San Francisco-based artist.

In the early 1980s, after a brief but intensive period of making work with relative success, the then 30-year-old US artist Hal Fischer abandoned making art. He also stopped regularly reviewing exhibitions for Artforum and Artweek and instead moved to curatorial and interpretative roles at San Diego's Timken Museum of Art from 1985 to 2007 and the Asian Art Museum Civic Center in San Francisco. Prior to this, he showed in the commercial galleries of San Francisco, largely in connection with a small coterie of structuralist photographers including Lew Thomas and Donna-Lee Phillips, a group whose concerns combined text and image to open up a set of possibilities that dealt 'with the social mediation of the physical world through', as Victor Burgin observed, 'the agency of signs.'

The signs in Fischer' work are specifically related to the guy culture that incrensingly saturated the Castro and Haight-Ashbury districts of San Francisco. His work spans what is often seen as the heady, liberatory period between the Stonewall riots and the advent of HIV/AIDS, and the first wave of publicly debated US legislative developments that came to shape queer contact to wider society; indeed, how these often radically political, social and historical events intersect is pictured in Fischer's series of images. Whether disseminating or withholding what was then a subcultural issue, a quietly radical metonymy of a scene is formed in the work. Fischer incorporates a systematic approach to producing his works, one that bears a loose correlation with many artists during that ern, such as Nancy Gordon, Allan Sekula or the flowchart dissections of Stephen Willats - an attempt to titrate the otherwise muddy waters of visual representations and to return photography to common cultural artefacts made for thought and discussion.

For one such work, taken over 24 hours during a weekend, Fischer photographed a popular bus stop bench on 18th Street, fust 75ft from the corner with Castro street, on the hour, every hour. It is currently on show at Project Native Informant in London; the last showing of the work wns in 1981 in the exhibition "Photographs and Words' at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Shot in black and white, the long wooden bench unwittingly confers a minimalist presence, and is populated by a complex nexus of people who appear, reappear and move on over the course of a day; they range from an older generation of men chatting to each other to gay men sunbathing, from workers and shoppers to the homeless or those simply drifting without aim. Details build, accrue and dissipate, such as a bottle of beer appearing at the edge of the frame that seemingly remains upright for two hours before falling over. The casual, everyday texture of waiting for a bus is dissolved by Fischer who returns it as a subversive place of cruising for sex. Under the guise of waiting for a bus rather than loitering with intent, the permissiveness that is captured is also a moment of reassembling space on different, less authorised terms.

Underneath the images, Fischer writes diaristic, incidental details that occur, either seen or unseen, from revealing conversations with those who are on the bench, considering dinner or being offered the club scene drug of choice, Quaaludes. Functioning as a set of gossipy footnotes that frame and pace the reading of the images, Fischer's text does not seek to document lives as if from an otherwise undisclosed frontier, rather he foregrounds the off-screen, the partial and the semi-detached nature of involvement with many of the subjects he observes. The choice of a bus stop buses offering the cheapest practical wny of travelling around a city - not only allowed Fischer to capture a snapshot of who moves through the city, but also produced a different sense of moving through it. 'In the blink of an eye; Herve Gulbert observed in the early 19808, 'the bus encompasses a multitude of bodies, faces, movements, and attitudes. It is like the large eye of a fly, a many-faceted eye, a rotating eye, if we think of each facet of the insect's eye as being characterised by a distinet image' In Fischer's work, such distinctions seem to lose footing the more drunk we become the more pills we take or the later the hour.

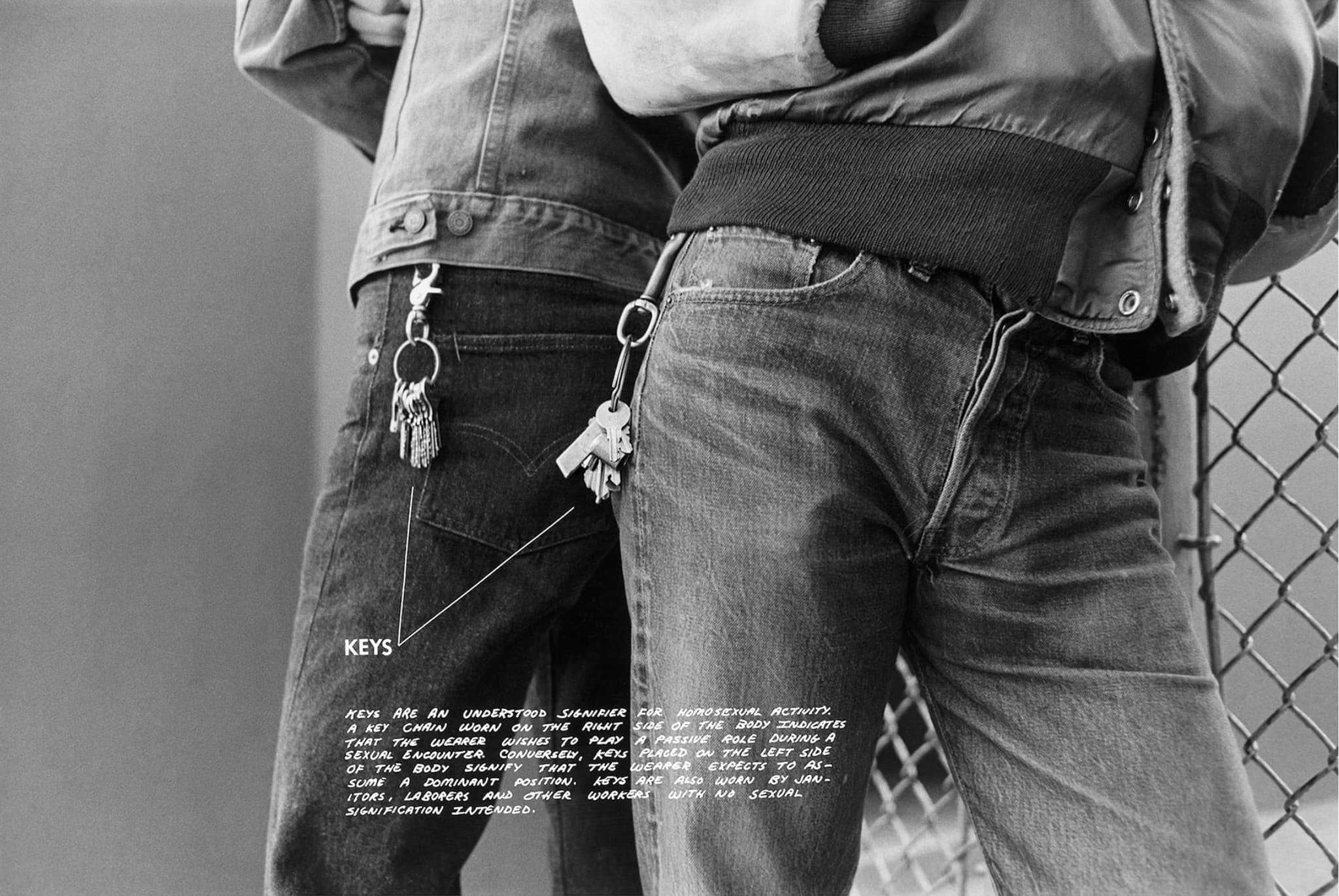

Fischer has described how viewers need to get close to his work in order to read the lettering inscribed on or under the images, forcing unexpected confrontations with graphic or sexualised descriptions. Part of Fischer' interest is the way language structures an identity but also how it fits around a subject. Typologies of bodies and codes previously unknown outside subcultures make up Fischer' most well-known series, 'Gay Semiotics';, currently on show at GOMA, where the artist provides something akin to a manual or map to a gay scene. The casual portraits, made up mostly of Fischer's friends, form an index of types within the San Francisco gay scene (which by virtue of its dominance perhaps led to its common vernacular among many urban scenes across the US, the UK and Europe). The images are later surveilled by Fischer who, with painstaking clarity, marks on the surface of the image the various signifiers the wearer might be suggesting - for instance, from hankie codes, keys or earrings, from colour to the placement on the left or right on the body, which indicate certain preferences. Fischer relays the possibility that a red handkerchief in a back pocket might indicate a taste for fisting or, rather dryly, that it might also indicate a nasal discharge. Fischer acutely aware of the pay offs and gambles of languages that hover outside more regulated interactions, not lenst the labour of guesswork. The series, subdivided into further categories 'Signiflers', 'Archetypal Media Images', 'Fetishes' and 'Street Fashion' - lightly presents how bodies yield information through their differences from others around them. By pointing out how in subcultures repurposed everyday objects signal alternative lives, a linguistic rubbing-up is made apparent from coded obliviousness. The appraisal of these 'clones' - men who wear codes to indicate sexual tastes and interests - augments the often hostile and derogatory representations found in mainstream media and the oncoming stigma of HIV/AIDS.

Even within this seemingly emancipated scenography, however, we come to see an entirely gay, white male index of identities. As Fischer recalls, 'this was culture that, at that point, was young, gay and white'. The dominance of this group points to how people of colour, or indeed women or trans, were, and continue to be, marginalised. The continuing project 'Cruising the Seventies', which includes numerous seminars that have taken place in Edinburgh, Warsaw and Berlin, similarly points to a continued Interest in what the period still holds. As the African-American writer Samuel Delaney recounts in his 1988 memoir The Motion of Light in Water, 'history is what we create by scratching, the annoyance, the irritation of writing, with its aspirations to logic and order, on memory's uneasy and uncertain discontinuities'. Fischer's life and work mirrors the incomplete and partial accounts of how queer lives and activities are recorded or scratched.

Chris McCormack is associate editor of Art Monthly.