PORTRAIT SHANZHAI BIENNIAL: Fake It Till You Make It

October 2015

Questions of appropriation have never been easy, but the New York-based artists collective Shanzhai Biennial uses the strategy of the copy – or, better, a copy of the strategy – as a way of refusing easy categorization, whether as parody, masquerade, parasitism, critique, or something else. Their work raises questions about the spectacle, globalization, branding, and, as Harry Burke argues, compels us to reconsider the relationship between art and image.

Tote bags; glossy catalogues; VIP cards; private, tinted cars; waxy trees in the foyer; invitations to dinners and afterparties; most biennials or art fairs (Frieze™, Basel™, Venice™, Independent ™) can be better described as lifestyle brands. For an affair that by design facilitates the sale of unique, highly reified items, they throw a lot of ephemera at you.

But this ephemera is hard at work. Sat streetside three days in, the drugs worn off, your phone dead – essentially, the moment the image breaks down – and you’ll notice this ephemera for what it is, an image. But what kind of image is it? It’s not an image that’s easy to see from a single vantage point, because it is an image that consumes you. It’s the image of the lifestyle brand itself.

Lifestyle brands are an attempt to sell an identity, or an image, rather than a product and what it actually does. And it’s possible to see the artwork as a product that also does something, for example bestow status, create aura or value, feed discourse or inspire political change. But how productive is this thing once usurped by the apparatus of the fair, which arguably does many of the above to a greater extent? Once the image in question is no longer that of or in the artwork, but the image of the viewer’s and artist’s and everyone else’s involvement in the social body that produces the artwork?

HOW CAN AN ARTIST REPRESENT THIS SOCIAL FORMATION AS A VISIBLE OR TANGIBLE ENTITY UP FOR CRITIQUE?

Founded in 2012, Shanzhai Biennial is an art-fashion crossover “meta-brand” co-directed by Cyril Duval, Babak Radboy and Avena Gallagher. Self-described as “a multinational brand posing as an art project posing as a multinational brand posing as a biennial,” their name refers to the Chinese phenomenon of shanzhai – the imitation and pirating of popular, often prohibitively expensive, brands – through which they détourne the endgame logic of the art biennial, comically self-identifying as a biennial in lighthearted knockoff of the format’s all-too-aspirational status. Their work frames the meta-signifying structure of the brand as a condition of contemporary creative production, and questions what autonomy can be found within that.

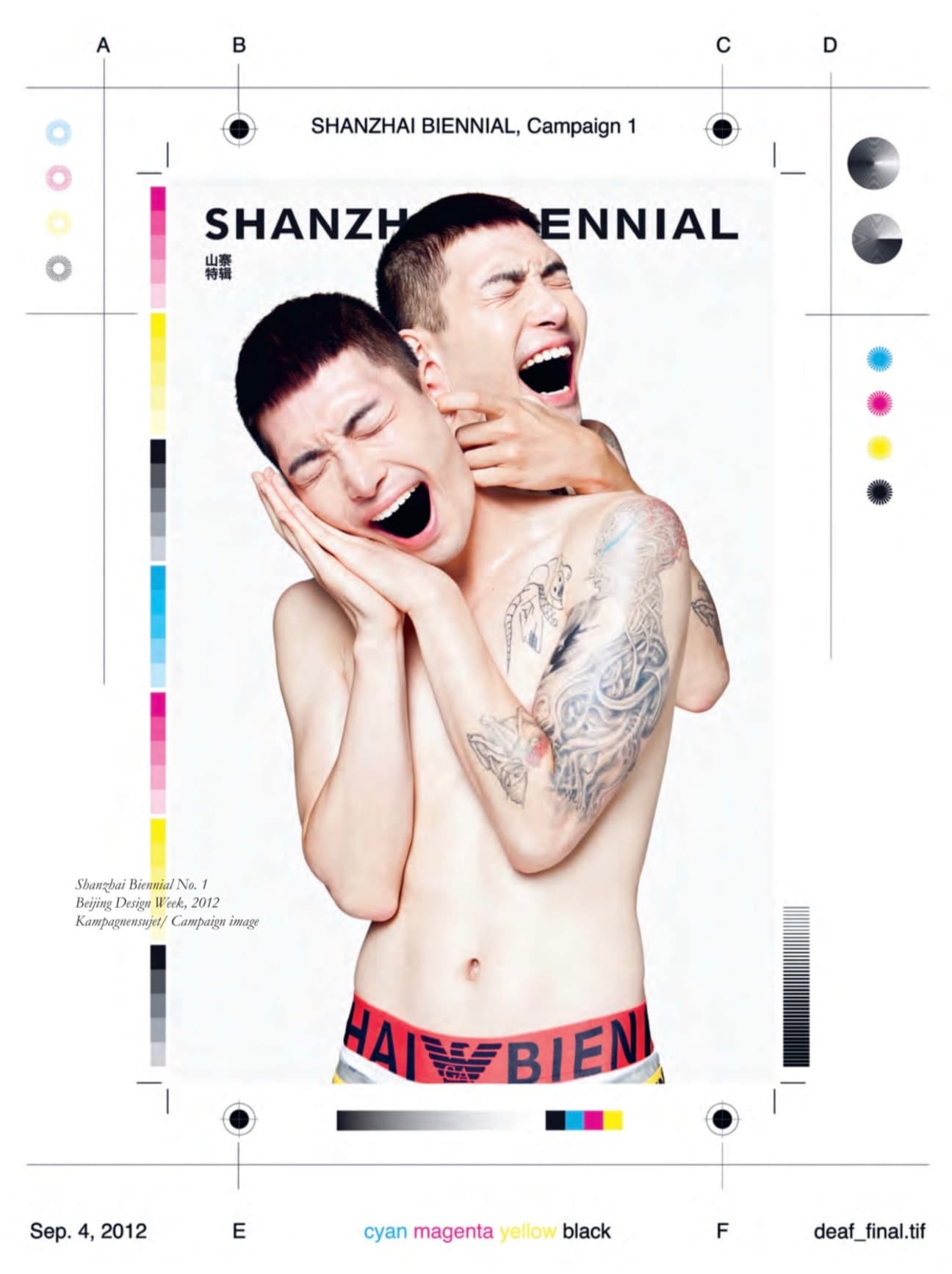

Their first project, Shanzhai Biennial No. 1 , saw the launch of a fashion line at Beijing Design Week in September 2012 – a collection that existed solely as campaign images on ceiling- high light boxes in a locked, high-windowed room. For their second, Shanzhai Biennial No. 2(2013), commissioned for the Josh Klinecurated exhibition “ProBio” at MoMA P.S.1, they produced an LED curtain which looped a video of actress, model and “conceptual artist” Wu Ting Ting lip-syncing distorted Mandarin lyrics to a version of Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” (which in turn inspired “Shanzhai”, the opening track to Fatima Al Qadiri’s 2014 debut album Asiatisch). Most recently, in Shanzhai Biennial No. 3: 100 Hamilton Terrace (2014), they attempted to sell a £32,000,000 mansion, 100 Hamilton Terrace, London, in their booth, with Project Native Informant, at the Frieze Art Fair in London. Their presentation seemed to sidetrack art even in its placement, in that you accessed their sales room-like booth, which performatively interlocked the worlds of wealth and theatre, before even entering the fair. Shanzhai culture’s cute consumer goods make apparent the otherwise invisible, and always volatile, relations underlying any trade. Shanzhai Biennial’s artworks ride on this, yet suggest that if the current end point of cultural production is the reproduction of the event as image, then, in the emancipatory logic of pirating, this image, and in turn the social formation that it stands in for, can be reimagined.

But their work does not simply remix a certain cultural form – be it fashion collection, biennial, music video – with the kind of ironic or performative twist that a more suburban post-punk attitude in recent contemporary art might have found appropriate. Shanzhai culture, though tempting, with Western arrogance, to dismiss as made up only of cheap knockoffs, is a sophisticated and intricate business. In New York artist Zoe Leonard’s arresting photographic project Analogue (1998–2007), pregentrification mom-and-pop stores, which appear too local to have ever left the block, are traced from 1990s Lower East Side through Africa, Eastern Europe, Cuba, Mexico and the Middle East. Today’s shanzhai products on, say, Manhattan’s Canal Street (a mecca for cheap goods frequented by artists working in galleries and studios nearby) share equally complex genealogies of signification. This was probed in Shanzhai Biennial No. 1 , which “counterfeited” contemporary Chinese artist Yue Minjun’s notorious paintings portraying himself captured in frozen, wide-mouthed laughter. Transferred from the context of Chinese “cynical realist” (a term used to describe Yue’s work that he himself rejects) painting to Shanzhai Biennial’s bright, slickly produced campaign stills (shot by New York photographer Asger Carlsen), these chalkily referential images suggest that the edges of the artwork, as indeed the logic of the brand more generally, spill over into, and thus are accountable to, extensive and entangled global geographies.

WE CAN’T TALK ABOUT THE ART FAIR OR BIENNIAL, OR EVEN THE “ART WORLD”, WITHOUT SIMULTANEOUSLY TALKING ABOUT GLOBALIZATION.

Yet the deeper questions of what that globalization is or how we talk about it are rarely successfully posed. Despite, or because of, an industry of criticism surrounding it, “globalization” remains at best a set of hypotheses, and something that operates more clearly packaged as ideology than worked through as actual, inherently messy and fragmented relations. This messiness is frequently ellipsed – not only circumscribed but also elided – by the art fair/biennial, despite its pretensions to discourse, as a standardised, financialised format exported globally to cultural centres as they attempt to share in the forms of capital gained from being on the art map, a power dynamic mirrored in the desire, even necessity, of young artists to participate in this format as the top-trending arbiter of success.

Amidst their exploration of the economic allure of the fake, and surely the fakeness of economic allure, there is an honesty in Shanzhai Biennial’s co-option of this hegemonic format, and their wont to reveal, to revel in, some of its underlying messiness. Shanzhai Biennial No. 3 dresses the Frieze Art Fair, tongue tightly in cheek, as little more than a spectacle in which to market absurdly expensive real estate; the sales desk was replete with limited-edition commemorative keys and haute-couture Frieze Art Fair totes. Yet there is no better city than London to illustrate the extent to which artists, like many people born into austerity and precarity worldwide, are held ransom to the relentlessly crushing property speculation of the 0.1%, and no better event than Frieze Art Fair to illustrate the ouroboros by which artists are then made, bless fate and irony, complicit to this.

Marketplaces built on an attention economy – such as, increasingly, the art fair, biennial and social network alike – have a tendency to reduce social relations to an image. What, then, can we draw from Shanzhai Biennial’s practice as critical image-making? Their work explores an expanded image that is more akin to the work of fashion designers like Telfar Clemens, with whom Shanzhai Biennial have collaborated, or artist collective GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council), than that of the traditional studio artist. These artists and designers create dynamic, expanded identities: expanded in the sense that they approach social factors that lie outside of the formal borders of the image – the racialised, globalised, spectacularised system of relations that codes the art fair, fashion shoot or indeed the white, Western eye as a norm – as an imagistic territory; and also expanded in the sense that this calls for extended accountability. As opposed to appealing to the supposedly neutral subject of a flattened, circulating image – the reified, courtly image that the Internet, the gallery and the art fair often cater to – their work calls into account the roles of artist, viewer and bystander in producing the social field that encounters this image as an artwork, and, in doing so, gives it so much meaning. An image is a contested territory, and a system, when itself presented as an image – even with the power that capital might invest in it as a “brand” – is equally contestable; ripe for intervention, resignification, or, with a little more humour, bootlegging.

Harry Burke is a writer and Assistant Curator & Web Editor at Artists Space, New York.