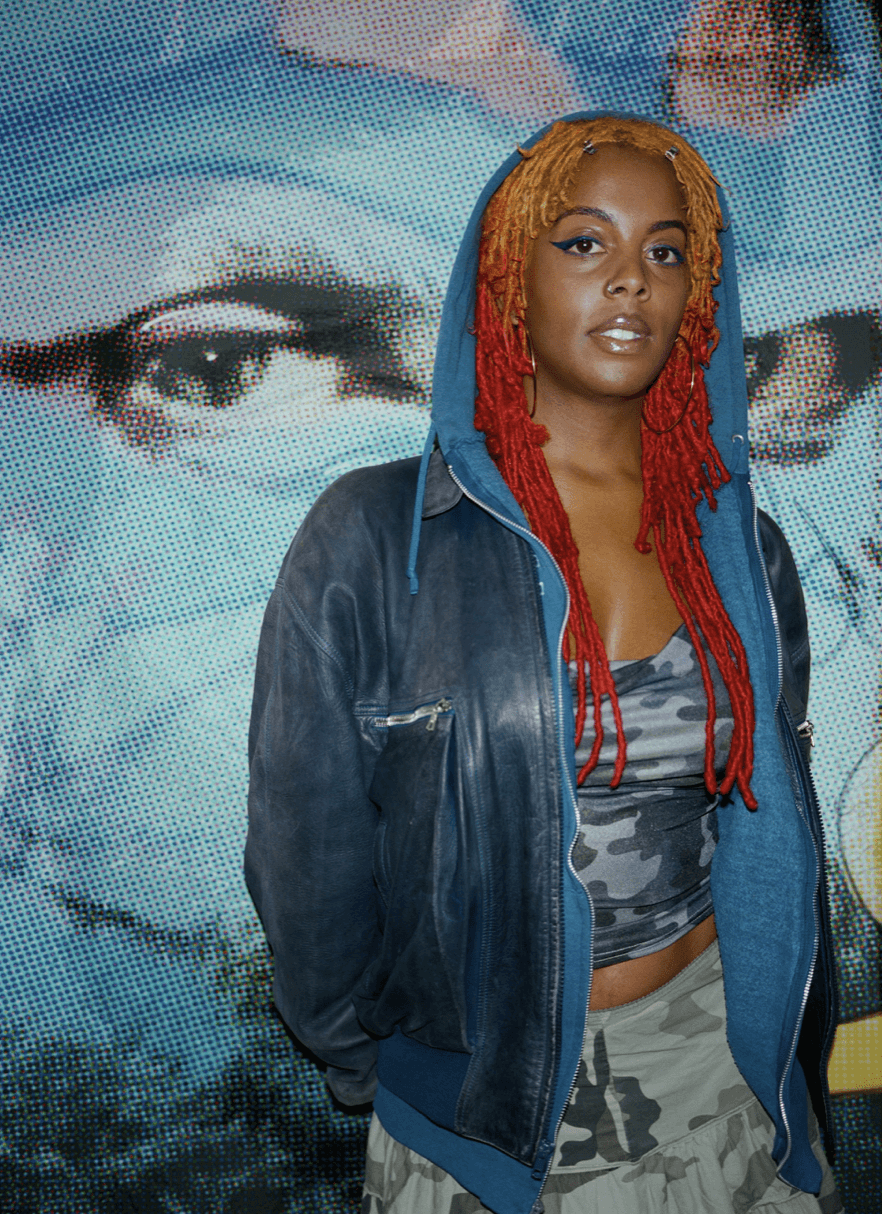

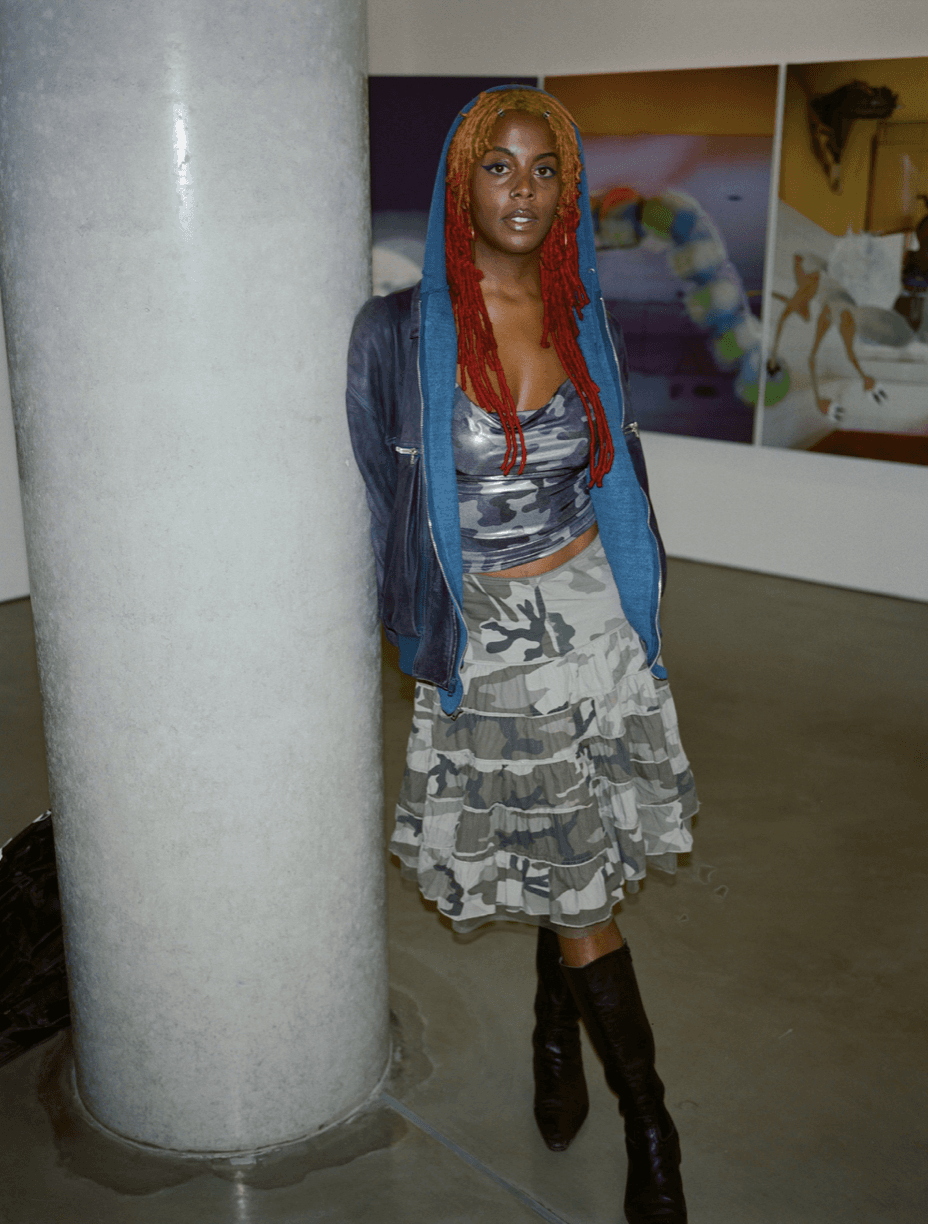

Embodying my ideas: Juliana Huxtable in conversation with P. Eldridge

November 2024

Juliana Huxtable and I meet at her exhibition in London, a week before the American election. I’ve been speaking with her studio manager for a few months, trying to organise the perfect time to speak with one another, deciding together it best to collide in person. Questions I have been forming fade away, instead of specifically focusing on Mucus In My Pineal Gland, Huxtable’s first book of poems and essays, we speak also about the exhibition, writing, her psychoanalytic influences and career thus far. I get a text that she'll be half an hour late and her gallerist decides to show me into a side studio where I can view Huxtable’s new work. The dichotomy of work presented between what is exhibited and currently in process encapsulates where our conversation slips into: how so much of what informs Huxtable’s work, the transference between the digital to the material, is evidently found within the play of making. What follows is a conversation that is strikingly intellectual as it is personable. I’m mostly taken by the sentiment, as emphasised in the title, of when Huxtable says, “I’m really good at embodying the ideas that I want to embody.” Undoubtedly, Huxtable reveals how the mechanisms of embodiment work for her through stream of consciousness writing, digital anarchic archiving, diaristic experimentation in the studio with her band Tongue in the Mind, and taking herself to remote places to dredge up — she, on the precipice of — her next publication which is all about the erotic, pleasurable, anti hetero patriarchal: love.

P. Eldridge: Your practice has focused on you as the primary figure across your art and photography. There's been a shift away from that to focus on your friends and band mates, which is really beautiful to see. There's this fatigue in having to constantly affirm your identity in your work, with people who question it as the centripetal force of everything you do, rather than getting to the crux of things; the themes in what you're trying to express of yourself now. To begin, I want to know: where are you now and how has your practice evolved by moving on to other subjects, by not losing your identity politics in them, but projecting and sharing them on and with other people?

Juliana Huxtable:

I never set out to make work that was about who I am in the world.

That was never my intention. When I was an undergrad, I did my thesis on the impossibility of having a stable identity as an intersex person. The literature I was reading framed my early thinking and phases into art making, where I wrote about Herculine Barbin. They are the first medically documented case of an intersex person during the early Victorian era and they were writing at the time.

Their diary is really intense. They've become this canonical figure in both intersex history and the medical history of intersex people. Foucault famously republished Barbin’s memoir, Herculine Barbin (1980) with an introduction.

So much of Barbin’s diaries – and other writings – are about the impossibility of identification and the impossibility of identifying with the I necessary to write from a subject position; which I can relate to. I never felt as though I fully inhabited an identity in the past, but now I feel more grounded in one than I did for most of my life; likely because, for a long time, my material or physical embodiment felt very in-between. Puberty was difficult for me because of my condition, and art making, the fluidity and the play with different kinds of avatars, was coming from a place of not identifying our disidentification.

It's not necessarily out of necessity either.

I don't think of it as out of necessity. If there is a necessity, it’s definitely not to express something that already exists as coherent beforehand. And ironically, I went into a lot of Freud, Simone de Beauvoir, and Judith Butler, who are all people working within psychoanalysis.

i was actually frustrated by a lot of the canonical writing and psychoanalysis on intersexpeople being really barbaric and cruel.

Everything I make is coming from a place of play and exploration, and I feel an inclination towards experimentation and putting on different avatars because I'm like, well, if there's no real essential essence that I feel an obligation to represent, then I can do all sorts of things.

I obviously have cultural identities, I have personal histories that inform how I move through the world and think. But more than anything, it is the spirit of experimentation and play, thinking through Barbin’s writing about the difficulty of identification, having a stable subject position, questioning what is the I? I don't feel like I have an I, it’s already such a sexualised object. There’s this struggle that’s there, for me, and ironically, so much of my early writing came out of me getting ready to party, playing with well, who am I today? It’s through dressing and accessorising – which people deem shallow fashion bimboish behaviour – that I learnt to have a constellation of ideas and references. My early writing was literally developed from a place of ‘putting on’ an identity, playing, and dressing from a subject position.

What I was so excited about, especially during the early Tumblr era, was the chaos and anarchy of everything, and the slippages between so many different things. To produce work from that – which to me at its most conservative was maybe about assemblage or iconoclasm – and then be like, oh, this is about a black trans woman, wasn’t enough.

It’s not enough at all. They’re not really seeing you, rather, they are reading your bio and sensationalising your identity as something that can be openly critiqued and scrutinised. Drawing out an existential struggle, as a black trans woman, from your work, it’s completely unhinged.

It's not enough! It also just showed the absolute shallow commitment that people were really engaging with trans and black people.

It's illiterate.

Yes! I went through a period where my output was more like my first solo show, A Split During Laughter at the Rally, at Reena Spaulings in New York, 2017. There was none of me in it at all. There was just my disembodied mouth – in a video I made – that would occasionally appear, there was no representation of me directly at all. That felt really important. And a lot of my early work, including my first show in London with Project Native Informant in 2017, included references to me, but generally speaking I was not in it. It was either text or graphics that were made to mimic screen printing, wheat pasting, whatever the themes I was dealing with, I really wanted to remove myself from that.

The thing is, I’m really good at embodying the ideas that I want to embody. I don't want my practice to ever just be overcome by reactiveness. Sure, it's important for me to understand the context that I'm in, and I want to feel like I have agency within that, but I don't want a purely reactionary practice. I moved back into self-portraiture but felt an inevitable projection of a biographical narrative onto what I do emerge. So for that reason, and also just because it's really intense to paint and photograph myself, I decided to make the practice more pleasurable and playful by expanding to the people around me. It instantly became more fun for me.

The digitization of your practice has been something that crosses form as well, it’s not something that just exists in your writing and first book, Mucus In My Pineal Gland. It’s across everything. There’s a really beautiful point in your exhibition text where you write: I am on my knees, mouth agape, a digital camera generated raw file in a PSD. It’s a beautiful and very fragile image, to be stuck in a Photoshop space, although it seems as if you enjoy playing there. I’m intrigued, why the digital?

I am inherently invested in the digital as a space of potentiality that can serve as a rejoinder to the lack of access, lack of resources, lack of training, and lack of exposure that so many people experience in regard to, especially in the arts, what is considered to be traditional. Traditionalism itself is something that can express so many class disparities and global geographic power imbalances. Even though the digital is obviously tied to the material, it's not like it exists as this floating space that's separate from it. At the very least, when I was growing up, it was really seared into my mind from my parents – who are both engineers – that technology was a means for black liberation. As long as you can get access to a computer, you can do anything. That's what I was raised on. Even though early on I wanted to draw and paint, my mother was like, anything that you do, you need to do it digitally. When I was old enough to use a mouse, she said, okay, you like to draw and you need to do this digitally.

Raised on Microsoft Paint, the best. [Laughter]

Yes! [Laughter] Literally, I’d draw on Microsoft paint. I used to make Microsoft Paint art and I would sell editions.

Shut up! [Laughter]

[Laughter] I would sell editions when I was younger and I would sell bookmarks where I had my Microsoft Paint art on the front with poems on the back.

Where are they now?

People have them, my godparents and people from my church growing up. Our family friends still have some of my art on their walls. Part of that was just my mother also being an engineer, saying, you need to be entrepreneurial and industrious about your artistic practices. She didn't believe in just making art for art's sake. So very early on, the digital was a space of potentiality and it came with a lot of aspirations, hopes, dreams. Although a lot of what I write about in Mucus In My Pineal Gland is about the realisation there are certain facts that cannot be disputed, it’s also about the failure and dissolution of a lot of what I saw as promises of the digital; particularly as they relate to rejoinder in the politics of history, epistemology and how knowledge is circulated, distributed in archives, how you can access things that are not always accessible. In the late nineties into the early two thousands I was so captivated, there’s literally just so much information online. As someone who is seeking out non-canonical, non- accidental histories, I realised I had access to all of that. But with the ephemerality of it all, and the contingency of it existing all on a physical database, I was aware that the digital seduces, by virtue, a kind of indoctrination into an ignorance and blindness to the materiality on which it's based.

If you don't have a server and if it collapses, if the person who uploaded the website doesn't pay for their hosting fee or they just check out and don't care, it’s gone. We’re also in a climate crisis. If we don't have water that's cooling these processing systems down, if we’re mining the earth for natural materials to create batteries, what’s going to happen to the information stored there? We are going to lose all of these histories. Or, we lose touch with all of these alternative narratives that not only shape digital culture, but shape the people that are using them. Like trans people, people of colour, people with unstable access to education, health and housing. You can obviously sense the fragility in the digital, how does that then make it into your physical work?

I've always had a conscious anxiety about the ephemerality of the digital.

As a kid for example – at my house in Texas, I cannot wait to finally get this stuff from my mum’s house – I have archives of videos and websites that are just melting in a garage. I would take websites – a lot of the websites that I'm constantly referencing that are the inspiration for many of my works – and print them out or save them to hard drives. In my room I had printouts of all of the websites because there was this urge to preserve the physical copy, maybe as a facsimile, maybe as an archive, maybe even just in the way that you have a photograph of someone that you love. There's both a practical and romantic relationship to the translation of digital into the material. That has grown and has turned into a kind of fixation and maybe even a fetish that informs everything that I do, because so much of how we interact with the digital – at least for me through computers – is through a screen. It’s inherently tied to the history of painting, photography, windows, film. The process itself begins with me painting someone. I photograph them and bring that into a digital space. I paint and print over it and then physically paint over it multiple times again. It's almost mania, this fixation with whatever happens within the digital needing to then be rendered into the material.

How does that anxiety make its way into the process of making music with your band, Tongue in the Mind?

We're working on the album now, and some of the songs themselves are journeys through this anxiety. There's one song that starts off just acoustic, it's just Joe [Heffernan] on guitar and me singing into a dry mic. That's the beginning. Then it builds into this fusion of synths and these fun experiments.

The album, can you tell me more about it?

The album is coming. It's definitely taken longer than I thought it was going to. This winter we're doing an album recording bootcamp. Winter is always when I get the most done. It’s always been that way. When I’m static, I'm just going about my days in New York, in my house, in my studio.

You’re no longer based in Berlin?

I was doing both but I can’t be in Berlin right now.

The culture in Germany is psychotic, socially and politically.

It’s a political move for me. The right wing-swing is so palpable and the stuff that's getting out in the news is a fraction of what's actually happening on the ground. If you're not living there, you don't really understand how insane it is. The police and surveillance is really intense. Artists and people I know who are moved to organised demos, who are posting funds for Gaza, are being persecuted and attacked by the police. I have friends who are currently facing incitement to terrorism by the German government. I was being accused of being a ringleader for antisemitism. It’s insane what’s happening there. Right-wing groups are storming queer events, it's really just full blown Nazism. I feel for my friends who don’t have somewhere else to go. I tried living in Beirut for a year but now it’s being completely bombed by Israel. So, I'm going to be in New York for a while and I’d like to spend more time in London.

Next week we’ll know about America too. It feels dangerous everywhere.

New York is a hub, like a country within a country; which isn’t to say that you aren’t subject to the complete total precarity of America, it’s just unhinged in other ways. There's a real sense of community, the cultural blood and zeitgeist of New York is much more in line politically with where I'm at generally, even if that means it's very out of touch with America as a whole.

Mucus In My Pineal Gland seems to delve deeply into layers of identity and self-perception. Psychoanalysis often talks about a ‘split’ self – between the conscious and unconscious, the ego and the id. Do you feel this split informs your writing or is represented in the work’s fragmented, layered structure?

What’s funny about Mucus In My Pineal Gland – I don't know if this is true for everyone as a writer, because I know there are writers that are very intentional about constructing, I imagine this is probably different for people that are writing fiction or something – is that, I often just write. I go into the zone and think, let’s go, go, go, go, go, go, go. Mucus In My Pineal Gland in particular traces a period of my life in which writing was coming from such a raw place. Sometimes I look back and I'm like, wow, girl, you really were putting it all out there.

Fuck, I think about that all the time with my writing. I can see so clearly when I’m being revealing and withholding, when I’m yearning to be seen and what I’m avoiding.

I was putting it all out there. What's funny is at the time I didn't think I was doing that. That’s the element of writing I love, the unconscious is going to come through either way.

i think of writing now as a process of getting in touch with the unconscious.

I do a lot of free writing exercises.

Stream of consciousness?

Yes, automatic writing, using a prompt and giving myself five minutes. It’s really important to me, the idea of the unconscious always informing my work. I also think sublimation is really important, as an analogue for the way that metaphor can function in writing. But then there's also this element of the psychosocial.

frantz fanon has completely changed how i think about and approach writing. one of thefailures of conventional psychoanalysis is understanding the ways in which – and this iswhere identity does come in, where i think with blackness you are brought up thinking – you are always a representative of something outside of yourself.

You're always a representative of the whole of blackness somehow, even if that's not your intention. It's not to say that that over-determines reality, but that's such a major part of reality, that there's the psychosocial and the collective unconscious specific to a kind of cultural, racial ethnic identity. Beyond that, which is why I brought up Herculine Barbin, is this feeling of being outside of the conventional subject formation.

i feel that – especially as an intersex person, as a trans person – there's a level ofconsciousness, self-awareness and apprehension that really fundamentally changes your relationship to subject

formation and how it expresses itself.

Mucus In My Pineal Gland comes from a place of accepting those things and also really leaning into it as something that's interesting, generative, as a thing that leans into a kind of schizoid relationship to identity.

I love the idea of schizoanalysis and trying to understand the relationship between schizophrenia as a mode of being and how that might express itself. I come from a family with a history of schizophrenia. My mother was schizophrenic, in and out of institutions throughout my whole childhood, and I try not to rely on diagnostic models – fuck the DSM – but I think it’s useful as a way to provide language to certain modalities. I think of schizophrenia as a capacity. I don't know if it's biological or whether it's just because I was raised by someone like that, but there is a kind of unhinged mental space that I inhabit. All of these windows, whether it's Barbin, Foucault, Fanon and the psychosocial, thinking about the impacts of a highly racialised society, a manic society on blackness, on intersex people, and trying to incorporate thinking about the use of psychoanalytic models with schizophrenia; all of these structures are ways of fragmenting, multiplying, diversifying, and shattering conventional conceptions of subject identity which is why I produce writing from this place. That is the most interesting writing to me and it also feels the most true to not just myself, but of the historical period that we're living through.

Is that true of the new poetry collection you’re writing?

The new poetry book is interesting because, in a similar way to the profession of the visual work, there are certain facts that cannot be disputed towards the end of the book. It’s taking the fundamentals that have been developed in all of my writing, in Mucus In My Pineal Gland which was very introspective, and expanding that outward.

Interesting, so still diaristic?

I use some autobiographical personal experience, anecdotal stuff with my relationship to technology, but predominately use it as a vantage point to expand more broadly, doing larger surveys; consuming and ingesting everything from video games, the Encyclopaedia, Britannica, and the modality of an unstable subject position which forms an ingestion of what's going on around me; to form something like a social critique, although it’s not that entirely. I also explore human and animal encounters which acts as a space of

subject instability, but – which I’m keeping in mind – there’s a need to centre pleasure. There’s an aspect of love emerging. I mean, the title of the book is from an erotic love poem that I wrote for my ex. There's a lot of love poetry and erotic poetry in the new book.

Mucus In My Pineal Gland is really erotic to me. When I read it, I understood it almost as if it were my own diary. What is the difference between the type of eroticism in Mucus In My Pineal Gland and your new collection?

Fundamentally, it’s coming from a different place. I think that a lot of Mucus In My Pineal Gland came from a place of conscious and intentional disidentification from a queer rejection of conventional formulations of romance; a conscious irreverence towards literary traditions. I was a queer punk, like, fuck that. For the new collection, it’s all about pleasure and the love of language itself. I discovered I am militantly against all forms of coupledom, heterosexual romance, and nuclear family dynamics; my writing reflects this. I was in a really intense relationship that ended up in an engagement. It read as a screenplay for a really unhinged experimental 1950s German film, structured as a heterosexual relationship gone left with the addendum of being trans, but it always felt wrong as an addendum. I was in a space to write pure love poems, pure being a placeholder that easily fits into the conditions that most people are operating under romantically.

There’s a lot of that, an era of shameless, almost unselfaware love and erotic poetry. I move into hetero-dystopia and my experience of that, of questioning how the person who wrote Mucus In My Pineal Gland ended up living with a man who expected the free extraction of domestic labour. It’s unhinged, the whole experience was crazy. I completely lost touch with my orgasm, I couldn’t cum anymore. It became abusive and really conventional and I kept asking myself, how did I end up here?

There's reckoning with exceptionalism that everyone has to do.

I think most people who end up in abusive situations probably have a similar feeling. There's a lot of that in this new book. I struggled with the writing during that period, my old notebook was destroyed too, before I had the chance to digitise it. I lost a year and a half of writing and poetry – crazy love and erotic poems.

So devastating!

I was just in a full blown writer’s depression, mourning the loss of my notebook. But then also at a certain point it's like, are you blowing this out of proportion? I had to move on at a certain point. All of these things were happening at once. Then I'm like, am I overdoing it? Am I projecting onto this my general anxieties of writing a book?

You had to have a funeral for the book, to let go of what you lost to move on.

Yes, then concurrently, I was dealing with this space after my last relationship where it's like, how do I access desire again, play again? Because my entire erotic imagination, which is just linked to my imagination, was overwrought with the urge to psychoanalyse everything: how did I end up in this relationship where my sexual fantasy is wrapped up in this one man extracting total conventional femininity, conventional expectations on women, from me? I become distrustful of myself, of my own sexual desire if that's what got me there. I kept wondering, how do I liberate myself? How do I get to a space of Free Sex? Which is where the title of the song from the Tongue in the Mind EP comes from.

It's like a desire to access play, to unlink the imagination from the overdetermined pathological sexuality of hetero-dystopia. How did you regain your writer's voice?

It was through a process of experimentation – music helped – and forcing myself to publish little things here and there. Earlier this year, in the middle of my Asia tour, I had two weeks free. I've always wanted to take an adventure alone to a really remote place and so I went to Thailand. I did research, looking for the most remote island, and found somewhere that was difficult to get to. I took a plane, an eight hour car ride, and then a two hour boat trip to this island. It was so generative in so many ways just to be alone. I was reading so much, trying to write more. I knew what I had to say was somewhere within me. I started a poem and then got really stuck, so resorted to just writing and reading, constantly shifting between the two. I didn’t fully reach what I was working toward, but I left the island knowing I was at the precipice of the feeling. It wasn’t until I came to London in April that it broke through, I was like, this is it!

In the throws of Eros. [Laughter]

Yes! [Laughter] I'm also in love again for the first time, but it's a different type of love. It's less manic. I don’t feel the possessive impulse that comes from the anxiety over losing someone to something else.

Mmm, love in the place of surrender.

It's not monogamous technically, it’s a lot of things. I don’t have the language for it, but it's nice, it feels really sophisticated and I feel wholly myself and also in love, which is a new feeling.

Being able to be both – yourself and in love – at the same time is quite an interesting concept as well. We're fed this idea that compromise is the way that you develop healthy relationships, not only with a loving partner, but with friends, with family. And it's like, well, actually, what if I don't compromise, at the very least, myself? What if I meet someone who also doesn’t compromise on who they are too? There’s so much fertile ground there to share within, knowing then that the things you can compromise on are things like your time.

Yes!

Time as an offering, a gift.

Exactly. I’m really invested in undoing – to the degree that I can undo – the weird hetero training that came from being with men. Babe, you and me both. [Laughter]

[Laughter] It got to the point where people were like, you only do the straight guy thing. I was so shocked, I’m like, that’s never been me. I’m terrified if that’s what I’m giving.

Huge boot. [Laughter]

It’s a chop! [Laughter]

We can scratch this from the record but, queer men are also not exempt for their contribution to patriarchy.

Absolutely not. Some of my most intense experiences have been with queer men, that’s what I was writing about in Mucus In My Pineal Gland, how some of them can uphold hetero patriarchy. When I look back on my writing about them, I’m like, period.

[Laughter] The younger you devoured.

That’s the bitch I’m trying to be. [Laughter]