Dozie Kanu on Disrupting the Norm

February 2021

Dozie Kanu creates artworks that are disobedient and stubbornly slippery. They resist classification and exist instead as communicative or performative objects. These objects are filtered through a personal lens drawn from the artist’s lived experiences as a Nigerian-American and member of the diaspora, both anchored in a Blackness the poet Fred Moten describes, in his book In the Break: Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, as ‘an ongoing performance of encounter: rupture, collision, and passionate response’.

‘I think the future is really going to be more about self-governance, and more people taking ownership of themselves and their destiny, as corny as that sounds,’ says Kanu. ‘I think the elusiveness in my work and my own personal categorisation comes from a place of self-governance, and a disobedience rooted in having the authority to place myself wherever or nowhere.’

Born and raised in Texas to Nigerian immigrant parents, Kanu initially intended to study film-directing but shifted his focus to production design for film and theatre, receiving his BFA from the School of Visual Arts, New York, in 2016. Escaping the high living costs and profit-driven art market of New York, he is now based in a warehouse he converted into a live-work studio in Santarém, north of Lisbon, Portugal.

‘I learned not to be afraid of making sacrifices just by having immigrant parents, so I’ve always been pushed into thinking about things practically and pragmatically,’ he says. ‘In the beginning, I felt like I didn’t have agency to work within the art world, but I soon realised as I kept creating these objects that they were addressing issues around design and its history through performative gestures. So moving to work within the context of art as opposed to design has given me the freedom to explore and experiment more.’

Traversing a broad range of influences, including minimalism, fashion, Black culture and critical thought, Kanu reuses and transforms found objects, giving them a new lease of life. In hemorrhaged and made deaf, 2020, an anti-climb raptor spike emerges from a pipe in a found plumbing system. This is fused with an antique shower bucket shrink-wrapped in inkjet-printed images of album sleeves by hip-hop artists such as 2-Def, Black Dave, Ghetto Twiinz and Big Pokey.

Kanu also upends the functionality and usefulness of everyday furniture, such as in Chair [iii] (Crack Rock Beige), 2018, which consists of a concrete chair mounted on a car wheel rim. In Bhad (Their Newborn’s Crib), 2019, a baby’s crib takes a sinister turn as its conventional wooden frame is replaced with powder-coated steel and customised with a series of anti-vandal scaling spikes. I learned not to be afraid of making sacrifices just by having immigrant parents, so I’ve always been pushed into thinking about things practically and pragmatically. Making work from what is readily available to him is both a pragmatic and a necessary choice for this young artist. His approach was reinforced by a recent trip to Nigeria, where social and economic constraints tend to encourage the fast and cost-effective production of objects with what is to hand. There, Kanu encountered aesthetics rooted less in perfection and more in a rugged approach to making.

‘A lot of things that I observed had a kind of endearing messiness to them,’ he says. ‘This resonated with me because, in an entirely different context, I felt like I was dealing with some of these issues but [being educated and working in the US] meant I was always trying to make things neater, and minimalism was always hanging over me, rather than having to work in a more visceral and tactile way.’

Kanu’s first solo museum exhibition, at The Studio Museum in Harlem last year, curated by Legacy Russell, marked a shift from depiction and representation to explorations of material effects and experiences. Some of the artworks in the show embodied this newfound ruggedness and less-clinical aesthetic, as evident in Chair [ix] (For Babies), 2019, a found high chair sculpted over with concrete and pieces of aluminium sheet.

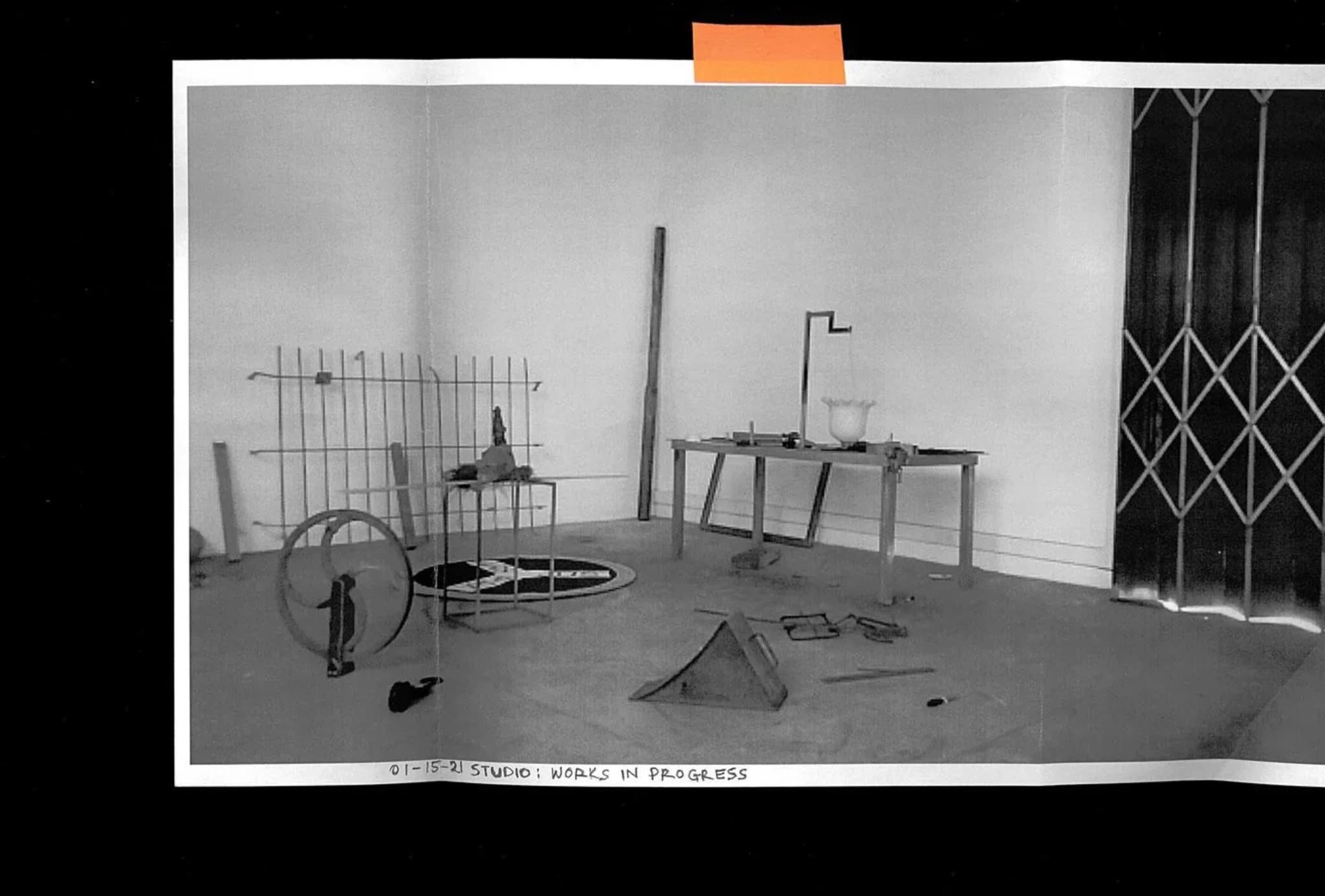

Kanu’s ongoing investigation into the limits of form, functionality, materiality and usefulness has seen his star rise in recent years. The attention is welcome, but he still wants space to experiment and fail: ‘I’m interested in making some kind of an impact within everyday life, even though my thinking is grounded in play and experimentation.’ He adds, ‘I still want to try different things that maybe don’t work, as failure is important for me to better understand what I’m doing.’

For his latest solo show, at Galeria Madragoa, Lisbon, Kanu continues his explorations of form and function in a series of sculptural experiments. But in future, he has ambitions to work on architectural projects as an extension of his studio practice, akin to the socially engaged and community-driven approach adopted by artist Theaster Gates in his rebuilding of South Side Chicago neighbourhoods.

‘I can’t at this point speculate too much on what that architecture might look like, but I imagine it will reflect a lot of what I do in my sculptural work around repurposing and creating in an environment founded by a Black mind that gives agency and allows free thinking.’

Conceptually and materially rooted in an ever-shifting contemporary approach, Kanu is all about new world-building, disrupting the norm and, importantly, rewriting stereotypical narratives around art-making by Black creatives who are too often defined solely by identity politics.

By Jareh Das