Devotional Doubling: Kenneth Bergfeld

August 2019

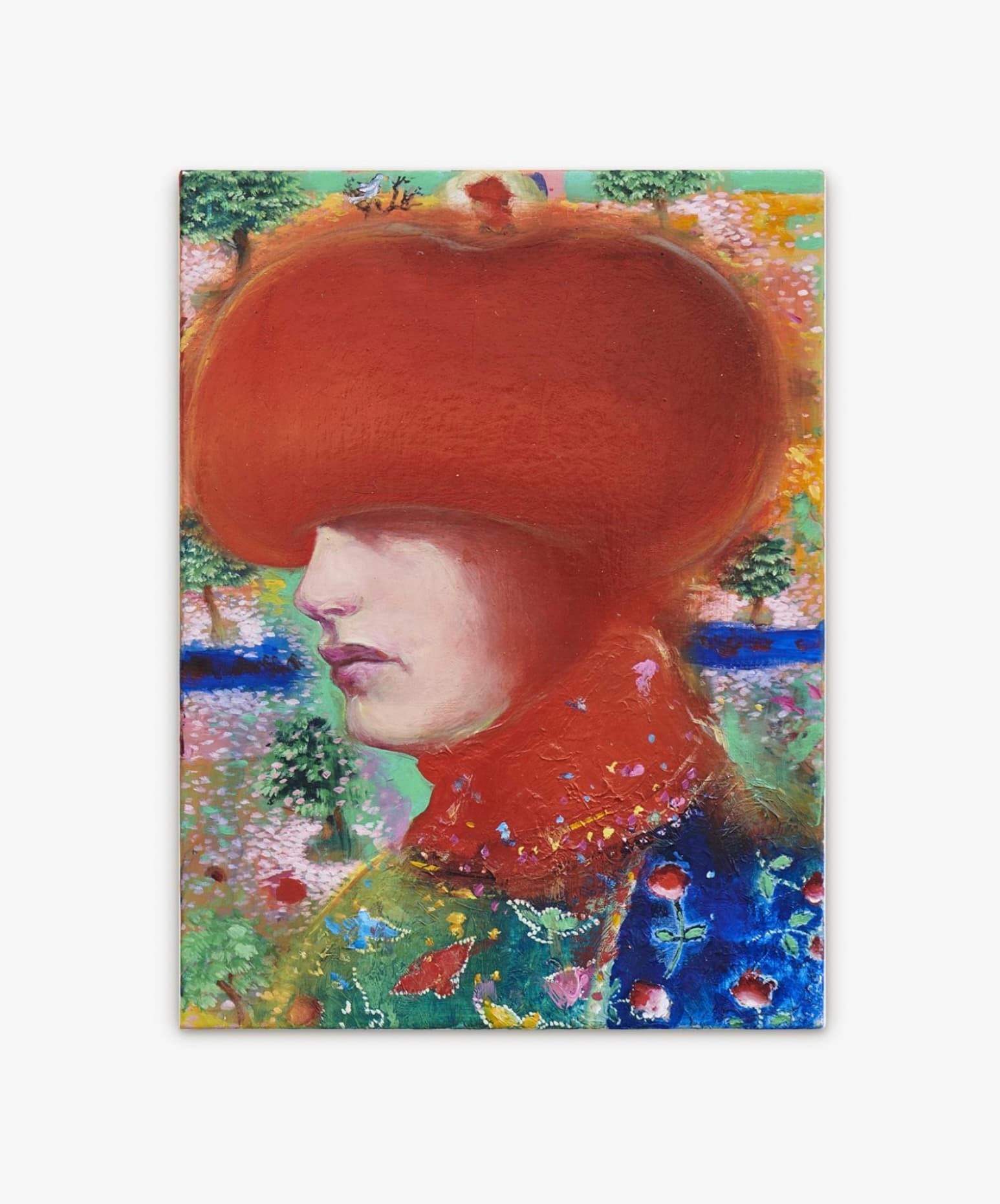

Dutch Mistress (2013) is profiled in softening summer-hot glow, her bowl cut snappish in cantaloupe orange. Her bouffant hair, plumulaceous, secludes the skull itself. What does the shape achieve? Powder puff, acorn, vessel, rotunda, halo. Holbein’s stoicism meets Steven Shearer’s boys of willowy lustiness—or Russian icon painting; the silhouette serves as a template for Androgynous Angels, a series of profile portraits modeled on and by Kenneth Bergfeld.

Inaugurating his Angels, Kenneth Bergfeld took a fancy to Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832), whose ombré skies and undulant clouds accumulate in Androgynous Angel VIII (2018). Repetition and attention intensify into saturation: if one pays attention, one sees “it” everywhere. William Gass knows this in On Being Blue by tracing the color it bleeds: “Russian cats and oysters, a withheld or imprisoned breath, the blue they say that diamonds have, deep holes in the ocean.” 1 Blue: private, cosmic, characteristic. Gorging on obsession, Gass’s attention becomes a portal, a fantasy you can almost step into. Bergfeld’s solo show, I, Spider at Project Native Informant, knows this: “I know now that it—I, Spider—was not about possessing, but about being possessed / by the forces that ran through me and this work unifying us eternally.” Each Angel is a twofold figure: Bergfeld viewing himself through the eyes of others. His lips—pink and beige and prominent—relay the constancy alongside each crest: a cloche-like cushion of luminous angora, it mushrooms into a dome, shrouding the head in a chatoyant shell. Each Angel is tailored to their environment. Angel VI (2018) is a princely apple of pulsatory red; trees littered with superfluous blossoms occupy the pointillist backdrop, in turn blurring into his turtlenecked torso of medieval gem embroideries. See, in other works, Georgia O’Keeffe white flowers floating in planetary blue, the face levitating; hair of beryl and seafoam green, its outline licked in flames; a tree of cinnabar lacquer deconstructing with branches lurching like antlers behind an angel’s crest of lynx-like spots splintered by spikes. Each angel is satiny and pearlized—with canvases primed repeatedly—encompassing, like a Raf Simons silhouette, a starched cowboy hat.

The repetition of form dissolves essentialism: it breeds difference. Bergfeld’s series’ most recent iterations, titled I, Spider (2019), resemble textual devices of mimesis. For Jacques Derrida, the text is always “double,” bowing to perpetual, infinite precedents, while for Roland Barthes, the text is woven, and in this making, “the subject unmakes himself, like a spider dissolving in the constructive secretions of its web.” 2 Yet through these very secretions, the subject resurfaces, albeit in disseminated form. Bergfeld echoes this; in his paintings’ independent reality, the self is deconstructed and strained by the existential. It is a scrutinizing reflection on color, texture, and structure over time, viewing one’s subjectivity through the eyes of others, as well as how one changes over such a period. It is this oscillation between repetitious form and form’s fundamental change that renders precision and extravagance, a combination of form and formlessness, a pristine structure’s lurch toward collapse.

Where icon painting emphasizes the eyes, Bergfeld erases the eye with a snowy orb; the lips, however, coax lyricism. Reinforcing the metaphysical relationships withheld by his angels, his spiders, Bergfeld has performed to his paintings with readings of messianic purple prose. For The Spire, Pt.1 (2018) at Hospitality, Cologne, Bergfeld adopted the persona of Kenny Unrest in an aural phantasmagoria: birdsong, little bells and stinging synths, talk on heat and stringency, the baking of challah, a violin’s bow. In a small loft populated by his plush-headed figures veiled at the neck with silk neckerchiefs, the effect echoes a woozy Carthusian cloister. Scenes of deep introspection worm into Bergfeld’s repertoire, reminiscent of Ezra Pound on his short imagist poems as concentrated equations: “record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective.” In a larger canvas, one stands in a heady violet marshland swathed with white calla lillies, great lounging leaves and magnified pansies—some stippled, others waterlogged. Monastic, the figure echoes Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s ethereal women unfurling into tulips, roses, and filigreed trellis, indivisible from their structure. Scarlet red, another sits among Impressionist roses, shadows swallowing the eyes, narrative spilling into the dark. Echoing Picasso’s Garçon à la Pipe (1905), whose original flowers sweep like wings, Bergfeld gestures toward the struggle of painterly justification. Made during Picasso’s Rose Period, the boy is immortalized. Rose: a period, a tone you see everywhere; no doubt it matches Bergfeld’s own attention, it is already double. On Bergfeld’s terms, it may also be devotional.

- Alex Bennett is a writer and editor based in London.