,

CAMP: Notes on Fashion

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Hal Fischer

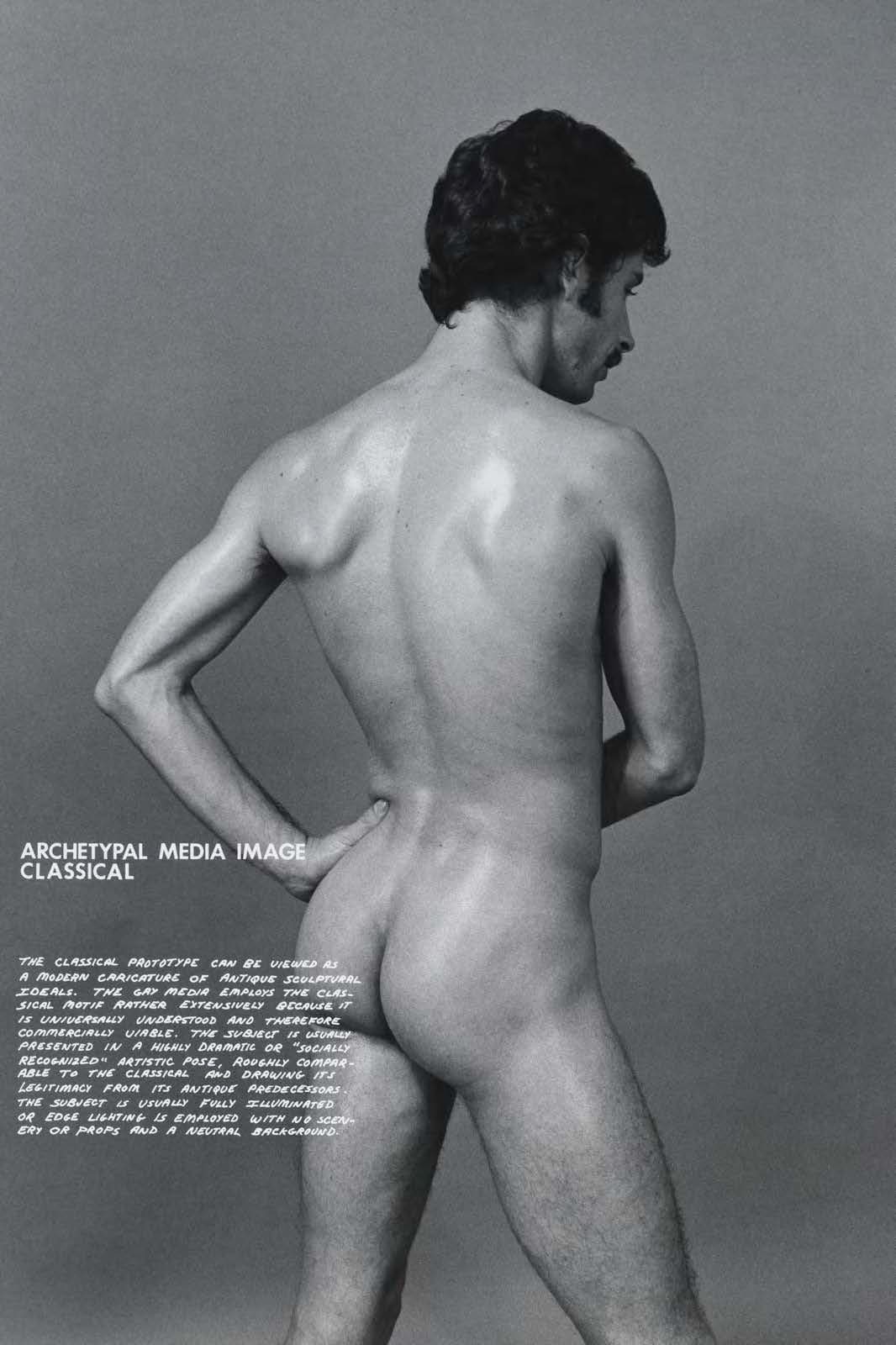

Archetypal Media Image: Classical

1977, printed 2017

Carbon pigment print

76.2 x 61 cm

30 x 24 in

Through more than 250 objects dating from the seventeenth century to the present, The Costume Institute's spring 2019 exhibition explores the origins of camp's exuberant aesthetic. Susan Sontag's 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'" provides the framework for the exhibition, which examines how the elements of irony, humor, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration are expressed in fashion.

Hal Fischer's work features in the opening gallery space, Camp Beau Ideal. In her seminal essay "Notes on 'Camp,'" published in 1964, Susan Sontag stated, "To talk about Camp . . . is to betray it." While an elusive concept, camp can be found in most forms of artistic expression, revealing itself through an aesthetic of deliberate stylization. As a site of the playful dynamics between high art and popular culture, fashion is one of the most enduring conduits of the camp sensibility. Through color, prints, patterns, materials, silhouettes, and embellishments, fashion both embraces and expresses such camp modes of representation as irony, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration.

Before Sontag's treatise, camp—as she asserted—was "something of a private code, a badge of identity . . . among small urban cliques." Her essay changed this irrevocably, catapulting camp into the mainstream, where it has remained ever since. There are periods, however, including the 1960s, the 1980s, and the era in which we live now, when camp comes to the fore as the defining aesthetic of the times. It is no coincidence that camp resurfaces during moments of social, political, and economic instability—when society is polarized—because, despite its mainstreaming, it has never lost its power to subvert and to challenge the status quo.

Through her "Notes," Sontag provided us with a grammar to analyze camp. That language is employed throughout the exhibition, which is divided into two sections. The first examines camp's origins, and the second explores the camp sensibility as it is reflected in fashion. It is a truism that the only point of agreement about camp is that there is no agreement, and this exhibition might raise more questions than it answers: "Is camp gay?" "Is camp political?" And, ultimately, "What is camp?" However, a point of growing consensus is the centrality of camp not only to fashion but to culture in general.

The "beau ideal" is an early nineteenth-century concept that describes the perfect model of male beauty, often exemplified by classical statuary. The contrapposto stance of these sculptures—characterized by the counterpoise of the shoulders, which turn away from the hip, and the resting of the weight on the back foot—helps to showcase not only symmetrical musculature and an idealized youthful athleticism but also a noble character, embodying the humanist ideal of an even temper. The arm akimbo, bent from the hip with the hand turned back, signals both power and relaxation.

Sculptures of Hermes, Ganymede, and Antinous (see the bronze on view here) are most often cited as examples of the beau ideal. Since the Renaissance, they have also come to be associated with male homosexuality, and as such have been endowed with the camp trace. Antinous, the young lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian (second century A.D.), was deified after his death and became a Hellenic idol of homoeroticism. From the seventeenth century onward, he served as a personification of male-to-male love. In the twentieth century, his contrapposto stance with arm akimbo became synonymous with the camp pose known as "the teapot."