Morag Keil: Limp Gestures

July 2023

For our focus theme “Opulence,” Hongkong-native writer and critic Elaine Tam dedicates her essay to the work of Scottish artist Morag Keil. She concentrates on two of their video works and a series of recent paintings to demonstrate how Keil manages to capture the opulence of simultaneity and ubiquity that dominates our present.

Style allies Morag Keil’s multidisciplinary work with our everyday media vernacular. Pedestrian in quality, you would be forgiven for mistaking Keil’s films for clips from a midnight YouTube binge or the slipstream of contentless videos that spread like an algae bloom. The unassuming feel of Keil’s films are her signature: an aesthetic bargained and bootlegged. Sparse and aloof, tattered and mangy, it is fair to wonder how Keil’s work could possibly be the subject of a meditation on opulence?

I read Keil’s work in this way to suggest that opulence, in essence, retains the sensibility of its past, albeit in an expressly different form. Sure, there is the kitsch mimicry of opulence that imbricates Susan Sontag’s Notes on Camp insofar as “camp taste supervenes upon good taste as a daring and witty hedonism.” Think glitzy diamante accessories, radical flamboyance, power clashing patterns, a reflexive much of a muchness. Then – and more interesting for my purposes – there is the sacerdotal motif of luxury hailing from the Baroque period: sumptuous and sinuous folds of cloth. A simple piece of fabric pleated announces its decadence through a cultural cachet of superfluity, using far more fabric than necessary for its undulations. The increased surface area, the resulting folds, is a decorative motif that hints at the aesthetic choice of excess at the behest of redundance and waste. Rending concept from mere innovation in lo-fi style, Keil’s filmic work points to the tightly sprung abundance of our contemporary condition, and advances through an uncoiling in space and time that proliferates multi-directional surface area, much like the Baroque fold.

Of all the advancements associated with the twenty-first century, the explosion onto the scene of a new world order might be best encapsulated by the plethora of internationally imported products you can find in an average kitchen. There is no more concentrated image of opulence than that which we conceal behind the white hygienics of glossy white cabinetry panels. This is what Keil’s seven-minute film Passive Aggressive 2(2017) seems to want us to know, even if she could also simply be engaging in mindless child’s play. Around she zooms – tailed, somewhat helplessly, by an adult with a handheld camera – flinging open the doors to the integrated storage of a modern kitchen and its refrigerator. The splayed doors frame mass-manufactured porcelain, nesting and chintzy; plastic trays of out-of-season blueberries; the potted exotics of the spice rack; typified organizers designed to the specifications of utensils – all of the normalized abundance we consider banal. No other trove better sums the aspirational worldliness which has characterized opulence, now commonplace and domesticated. Following the child’s loop around the kitchen island, the passage increasingly become assault course for the filmmaker who, wedged between the creation of these door-folds in space, returns in a later sequence to perform the same action, as if anxiously looking for something misplaced.

If reach has to do with travel, budget airlines and the development of cargo networks have invariably led to an extension of accessible surface. Where travel has not been possible, mass-produced goods flow through these transport networks to deliver the world to our doorstep. Inside the home, digital technology and the personal device has done something no less dramatic, though different in kind. With it we are afforded a portal – one undersigned by Keil’s startled jump cuts and framed webcam views – through which we can experience a dispersal, an everywhere-ness all of the time.

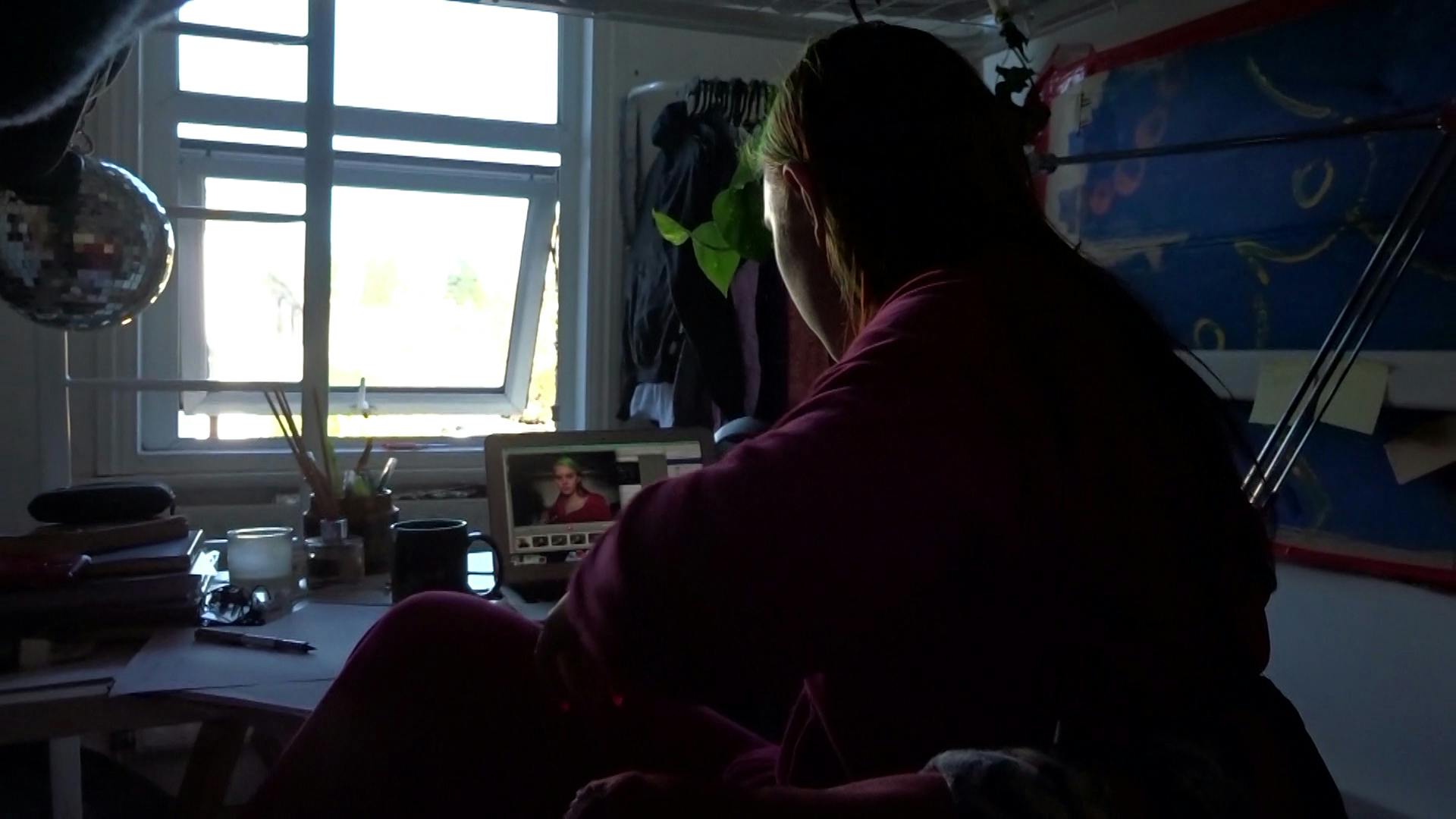

Amplifying the sense of our enmeshment with a world of appearances, the film dithers on a young teen with green-streaked hair moments after the kitchen scene. Listlessly she performs the simple act of taking a selfie on her laptop, which is shown to us from behind, through the view of the webcam, from beyond her laptop and from bird’s eye view. Reveling in the capacity of filmic vantage points to mediate and impart a difference in reading and meaning, Morag Keil appears to be both experimenting with and breaking down the component parts of the film culture we are familiar with. The duplicating effect of the range of camera angles again motions towards the pleating of a single reality while aping the multi-cam set-ups that are the cornerstone of ‘actual’ filmmaking. A segment of CGI (computer-generated imagery) in a latter part of the film sees an imaginary camera on an imaginary dolly hyper-fluidly navigate an impassive, irreal space. Cycling through a labyrinth of doors set within a green room, the scene opens onto other scenes of the same room, and still more doors, leaving the viewer with the feeling that the fold is also an ineluctable veiling – a simulacrum emptied of meaning. This clip of CGI anticipated Keil’s 2018 exhibition Here We Go Again at Project Native Informant, London, where the artist built an installation comprising HD videos, movement activation equipment, a home surveillance video camera and maze-y series of corridors that lead nowhere.

By contrast Keil’s Dizzy (2019) is an eleven-minute film premised upon one overarching concept. Equal parts mesmeric and nauseating, Dizzy is set within one floor of a shopping mall rotunda and involves teenagers holding forward-facing handheld cameras filming from chest-height. The viewer of the film takes up position as a zombified shopper; the camera is trained dryly on a unchoreographed path that snakes around rack upon rack of mediocre department store fashion. Jump cuts are determined by the teen protagonists, who occasionally bisect each other’s paths, prompting a switch in view to the passer’s camera, the new ‘player’ named in the bottom left corner. Occasional swooping angles conjure the dovetail of fighter jets. In place of diegetic mall humdrum, we hear the soundscape of the first-person-shooter game Call of Duty: the droll of rolling tanks, interruptions by tinny voice, the cascade of white noise that brackets it, the occasional whistle of a falling grenade that announces an explosion, other airborne or ambulatory clamor. Sound is what completes and makes Dizzy legible as a virtuality displaced and mapped onto the real space-time of the mall, with allusions to both opulence and war.

The ringed structure of Keil’s mall is also emphatically a carousel, so that we might speak of Dizzy as already implicated in the effect of its title before we even regard it as film. Much like the reveal of space through a pleating that is central to Passive Aggressive 2, Dizzy offers us a looping purgatory: the tyranny of an open world with limitless creation and no dead ends. Open world video games, generative algorithms and the ever-growing immensity of info-data attest to both a rapacious expansion and heady love of speed, but in turn also dramatizes an unstoppable entropy that introduces unintended consequences – a world which once again slips from our control. With the inception of the video blog and camcording sites, we opt into an invasion of privacy which sees the home becoming a site of performance not unlike certain of our public spaces. In this regard, all inhabitable space is prised apart to offer a blistering everywhereness at the expense of shelter from exposure, but Keil’s response to this reality is not without irony.

In a series of paintings from 2016, the artist has clumsily rendered the likeness of laptops, swiftly transposing the personal device to a domain of deactivation. There is something awkward about the choice of such paintings in that painting is itself an age-old device used to transmit imagery and information through generational time. Relegated to painting, the laptops disrupt the loop of 24-hour streaming, 7-day-a-week access. One afternoon at Keil’s studio, we discuss a new suite of works that she is currently working on and in which she plans to paint various digital photographs she has taken of her cameras. This unusual gesture entails a stand-off of stares: a camera photographs a camera resulting in an image rendered as painting for enjoyment by the eye. Keil’s new paintings are an ouroboric, self-defeating exchange of gazes at risk of unspooling ad infinitum, that is, until it exhaustedly arrives to its destination as analogue matter.

When Keil pauses, I think of the potential for everything to be gamified; the thresholds between reality and appearances; the opulence of a world that duplicates with every pleat; the spawning of virtual realms accessible by technological portals; and the deference to a multiplication by speed that distorts meaning. Speed is also answerable to the problem of the ultimate luxury: time. Be it a bid for immortality, a pledge against aging, or the 4-day work week, we use speed as a means of territorializing time because lack of movement or paralysis is in contemporaneity a sure sign of death. Against the allure of friction-less physical and virtual space, and contra seamless immersion by tricksy film editing, Keil’s DIY hatchet job films Passive Aggressive 2 and Dizzy complicate contemporary opulence by showing us manifold wrinkles in space and time.

If opulence is excess, and if excess also describes the numbing muchness of our existence in the simultaneous plural, then a return to the aesthetic sensibilities of the outmoded map out its possible exasperation. Keil uses what she describes as ‘limp gestures’ to appeal to the impoverishment of self-image, the abduction of the real, and the hapless quality of screen-based experience that trades the spontaneous for the scripted. There is no archness or spectacle about her material and how it is assembled – a disarming approach that breaches the world of appearances. The hack verbiage underpinning Keil’s practice dialogues with other of the artist’s personal activities. For example, a number of years ago, Keil was part of a ‘computer club’ offering pro-bono DIY repair jobs on laptops, doing simple things like changing their batteries or upgrading their RAM (random access memory) ‘for fun.’ In a similar vein, and drawing attention to the ‘black box’ of everyday technologies, she plans to run a workshop at Momentum 12 biennale in Norway, which will see participants undertaking life drawing of surveillance cameras and electrical boxes around town. This collective act of sousveillance – a term denoting ‘reverse surveillance’ coined by Steve Mann, a proponent of wearable technologies – alerts us to the presence of the unassuming opulence that services our everywhereness.

More than simply touting mainstream commentary about the evils of technology, media illiteracy, or idle consumption, Keil’s work engages with contemporary reality in terms of language and form. It is neither direct critique nor personal plight against opulence as contemporary currency; rather, it drives us towards thrifted futures and underscores the deranged humor of an impossible denouement.

Text by Elaine Ml Tam